18

Visibility

Visibility is defined as the greatest distance that you can see and identify objects — it is a measure of how transparent the atmosphere is to the human eye. The actual visibility is very important to pilots and strict visibility requirements are specified for visual flight operation.

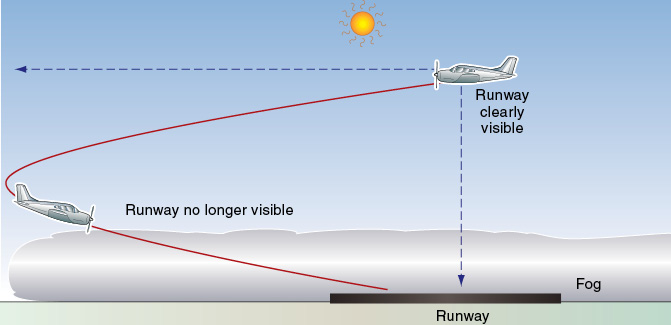

Slant visibility may be quite different from horizontal visibility. A runway clearly visible through stratus, fog or smog from directly overhead the airport might be impossible to see when you are trying to fly the final approach.

Figure 18-1 Slant visibility may be severely reduced by fog, smog or stratus.

On a perfectly clear day visibility can exceed 100 NM, but this is rarely the case since there are always some particles suspended in the air preventing all of the light from a distant object from reaching your eyes.

Rising air (unstable air) may carry these particles up and blow them away, leading to good visibility; stable air that is not rising, however, will keep the particles in the lower levels, and this may result in poor visibility.

Particles that restrict visibility include:

-

minute particles so small that even very light winds can support them;

- dust or smoke causing haze;

- liquid water or ice producing mist, fog or clouds;

- larger particles of sand, dust or sea spray which require stronger winds and turbulence for the air to hold them in suspension; and

- precipitation (rain, snow, hail), the worst visibility being associated with very heavy rain or with large numbers of small particles, such as thick drizzle or heavy, fine snow.

Unstable air that is rising may cause cumuliform clouds to form, with poor visibility in the showers falling from them, but on the other hand, good visibility with rising unstable air will carry obscuring particles away. As well as causing good visibility, the rising unstable air may cause bumpy flying conditions.

Rain or snow reduces the distance that you can see, as well as possibly obscuring the horizon and making it more difficult for you to keep the wings level or hold a steady bank angle in a turn. Poor visibility over a large area may occur in mist, fog, smog, stratus, drizzle or rain. As well as restricting visibility through the atmosphere, heavy rain may collect on the windshield and further restrict your vision or cause optical distortions, especially if the airplane is flying fast. If freezing occurs on the windshield either as ice or frost, vision may be further impaired. The refraction of light coming through rain on the windshield is approximately 5° and makes objects appear further away than they are. In terrain, for example, a hilltop will appear 260 feet lower than it actually is at ½ NM. During landing, the runway appears further away than it really is. This can result in hard landings.

Strong winds can raise dust or sand from the surface and, in some parts of the world, visibility may be reduced to just a few feet in dust and sandstorms.

Sea spray often evaporates after being blown into the atmosphere, leaving small salt particles suspended in the air that can act as condensation nuclei. The salt particles attract water and can cause condensation at relative humidities as low as 70%, restricting visibility much sooner than would otherwise be the case. Haze produced by sea salt often has a whitish appearance and may often be seen along ocean coastlines.

The position of the sun can also have a significant effect on visibility. Flying down-sun (with the sun behind you) where you can see the sunlit side of objects, the visibility may be much greater than when flying into the sun. As well as reducing visibility, flying into the sun may also cause glare. If landing into the sun is necessary because of strong surface winds or other reasons, consideration should be given to altering your time of arrival at a destination. This is especially true if the aircraft windshield is older and badly crazed. Seeing though the windshield under these conditions may not be possible.

Remember that the onset of darkness is earlier on the ground than at altitude. Even though visibility at higher altitudes might be good, flying low in the traffic pattern and approaching to land on a darkening field may cause problems.

Inversions and Reduced Visibility

An inversion occurs when the air temperature increases with altitude (rather than decreasing, which is the usual situation).

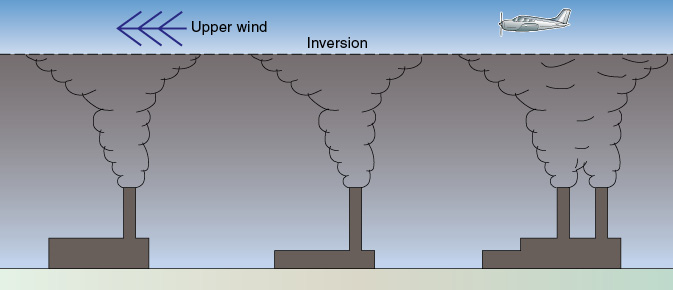

A temperature inversion can act as a blanket, stopping vertical convection currents —air that starts to rise meets warmer air and so will stop rising, i.e., temperature inversions are associated with a stable layer of air. Particles suspended in the lower layers will be trapped there causing a rather dirty layer of smoke, dust, or pollution, particularly in industrial areas. These small particles may act as condensation particles or nuclei, and encourage the formation of fog if the relative humidity is high — the combination of smoke and fog is known as smog. There is usually an abundance of condensation nuclei in industrial areas as a result of the combustion process (factory smoke, car exhausts, etc.), hence the poor visibility often found over these areas. Certain places in the United States are prone to this kind of visibility problem, notably the Los Angeles, California region.

Similar poor visibility effects below inversions can be seen in rural areas if there is a lot of pollen, dust or other matter in the air.

Inversions can occur by cooling of the air in contact with the earth’s surface overnight, or by subsidence associated with a high pressure system as descending air warms. The most common type of ground-based inversion, called “radiation cooling,” is produced by terrestrial radiation on a clear, relatively still night. Terrestrial radiation often leads to poor visibility in the lower levels the following morning from fog, smoke or smog.

Figure 18-2 Reduced visibility and smooth flying conditions beneath the inversion, and possible windshear passing through it.

Flying conditions beneath a low-level inversion layer are typically smooth (due to stable air not rising), with poor visibility, haze, fog, smog or low clouds. Because there is little or no mixing of the air above and below an inversion, the effect of any upper winds may not be carried down beneath the inversion. This may cause a quite sharp windshear as an airplane climbs or descends through the inversion.

High-level inversions are common in the stratosphere, but these are so high as to only affect high-flying jets.

Condensation

Visibility can be dramatically reduced when invisible water vapor in the air condenses out as visible water droplets and forms clouds or fog. The amount of water vapor which a parcel of air can hold depends on its temperature — warm air is able to carry more water vapor than cold air. Warm air passing over a water surface, such as an ocean or a lake, is capable of absorbing much more water vapor than cooler air. The horizontal movement of an air mass is referred to as “advection.” Fog can occur as a result of moving warm moist air over a cold surface, forming advection fog (page 410).

If the moist air is then cooled, say by being forced aloft and expanding or by passing over or lying over a cooling surface, it eventually reaches a point where it can no longer carry all of its invisible water vapor and is said to be saturated. The temperature at which saturation occurs is called the dewpoint temperature (or simply dewpoint) of that parcel of air. Any further cooling will most likely lead to the excess water vapor condensing out as visible water droplets and forming fog or clouds, a process encouraged by the presence of dust or other condensation nuclei in the air. If the air is extremely clean, with very few condensation nuclei, the actual condensation process may be delayed until the temperature falls some degrees below the dewpoint.

Air carrying a lot of water vapor, for instance warm air after passing over an ocean or large lake, will have a high dewpoint temperature compared with the relatively dry air over an arid desert. Moist air may only have to cool to a dewpoint of +25°C before becoming saturated, whereas less moist air may have to cool to +5°C before reaching saturation point. Extremely dry air may have to cool to a dewpoint temperature of -5°C before becoming saturated.

Clouds or fog form when the invisible water vapor condenses out in the air as visible water droplets. The closeness of the actual air temperature to the dewpoint of the air, often contained in METARs, is a good indication to the pilot as to how close the air is to saturation and the possible formation of clouds or fog. Therefore a wise pilot will collect, as part of the weather briefing, a series of METARs for specific airports to determine the temperature-dewpoint spread. A larger spread indicates a trend towards improved conditions, while a narrower spread is a sign of lowering ceilings and visibility.

If the water vapor condenses out on contact with a surface such as the ground or an airplane that is below the dewpoint of the surrounding air, then it will form dew (or frost, if the temperature of the collecting surface is below freezing).

The reverse process to condensation may occur in the air if its temperature rises above the dewpoint, causing the water droplets to evaporate into water vapor and, consequently, the fog or clouds to disperse.

Fog

Fog is of major concern to pilots because it severely restricts vision near the ground. The condensation process that causes fog is usually associated with cooling of the air either by:

- an underlying cold ground or water surface (causing radiation or advection fog);

- the interaction of two air masses (causing frontal fog);

- the adiabatic cooling of a moist air mass moving up a slope (causing upslope fog); or

- very cold air overlying a warm water surface (causing steam fog).

The closer the temperature/dewpoint spread, and the faster the temperature is falling, the sooner fog will form. For instance, an airport with an actual air temperature of +6°C early on a calm, clear night, and a dewpoint temperature of +4°C (a temperature/dewpoint spread of 2°C) is likely to experience fog when the temperature falls 2°C or more from its current +6°C.

At very cold temperatures, ice fog is created by frozen water particles put into the air from internal combustion engines. During cold weather operations this can lead to a significant decrease in visibility, particularly on a busy ramp area.

Radiation Fog

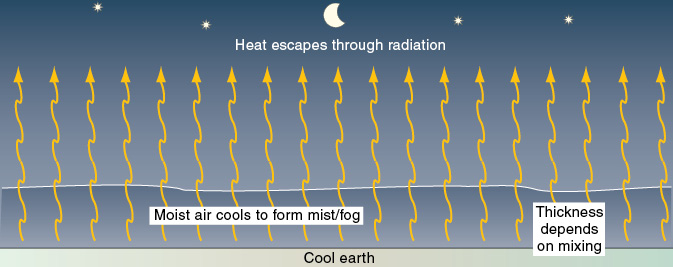

Radiation fog forms when air is cooled to below its dewpoint temperature by losing heat energy as a result of radiation. Conditions suitable for the formation of radiation fog are:

- a cloudless night, allowing the land to lose heat by radiation to the atmosphere and thereby cool, also causing the air in contact with the ground to lose heat (possibly leading to a temperature inversion);

- moist air and a small temperature/dewpoint spread (i.e., a high relative humidity) that only requires a little cooling for the air to reach its dewpoint temperature, causing the water vapor to condense onto small condensation nuclei in the air and form visible water; and

- light winds (5-7 knots) to promote mixing of the air at low level, thereby thickening the fog layer.

Figure 18-3 Radiation fog.

These conditions are commonly found with an anticyclone (or high-pressure system).

Air is a poor conductor of heat. If the wind is absolutely calm only the very thin layer of air 1 to 2 inches thick actually comes in contact with the surface will lose heat to it. This will cause dew or frost to form on the surface itself, instead of fog forming in the air above it. Dew will form at temperatures above freezing, and frost will form at and below freezing point. Dew may inhibit the formation of radiation fog by removing moisture from the air. After dawn, however, the dew may evaporate and fog may form.

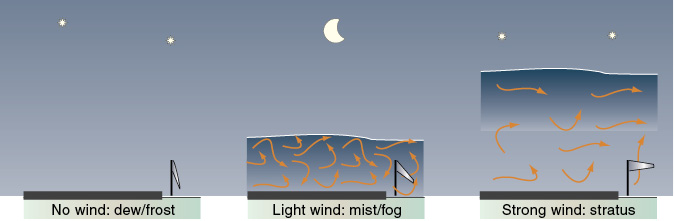

If the wind is stronger than about 7 knots, the extra turbulence may cause too much mixing and, instead of radiation fog right down to the ground, a layer of stratus clouds may form above the surface.

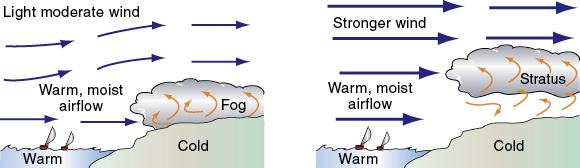

Figure 18-4 Wind strength will affect the formation of dew/frost, mist/fog or stratus clouds.

The temperature of the sea remains fairly constant throughout the year, unlike that of the land which warms and cools quite quickly on a diurnal (daily) basis. Radiation fog is therefore much more likely to form over land, which cools more quickly at night, than over the sea.

As the earth’s surface begins to warm up again some time after sunrise, the air in contact with it will also warm, causing the fog to gradually dissipate. It is common for this to occur by early or mid-morning. Possibly the fog may rise to form a low layer of stratus before the sky fully clears.

If the fog that has formed overnight is thick, however, it may act as a blanket, shutting out the sun and impeding the heating of the earth’s surface after the sun has risen. As a consequence, the air in which the fog exists will not be warmed from below and the radiation fog may last throughout the day. An increasing wind speed could create sufficient turbulence to drag warmer and drier air down into the fog layer, causing it to dissipate.

Note. Haze caused by particles of dust, pollen, etc., in the air of course cannot be dissipated by the air warming — haze needs to be blown away by a wind.

Advection Fog

A warm, moist air mass flowing as a wind across a significantly colder surface will be cooled from below. If its temperature is reduced to the dewpoint temperature, then fog will form. Since the term advection means the horizontal flow of air, fog formed in this manner is known as advection fog, and can occur quite suddenly, day or night, if the right conditions exist, and can be more persistent than radiation fog.

For instance, a warm, moist maritime air flow over a cold land surface can lead to advection fog forming over the land. In winter, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico moving north over cold ground often causes advection fog extending well into the south-central and eastern United States.

Advection fog depends on a wind to move the relatively warm and moist air mass over a cooler surface. Unlike radiation fog, the formation of advection fog is not affected by overhead cloud layers, and can form with or without clouds obscuring the sky. Light to moderate winds will encourage mixing in the lower levels to give a thicker layer of fog, but winds stronger than about 15 knots may cause stratus clouds rather than fog. Advection fog can persist in much stronger winds than radiation fog.

Sea fog is advection fog, and it may be caused by:

- tropical maritime air moving toward the pole over a colder ocean or meeting a colder air mass; or by

- an air flow off a warm land surface moving over a cooler sea, affecting airports in coastal areas. Advection fog is common in coastal regions of California during summer.

Figure 18-5 Fog or stratus caused by advection.

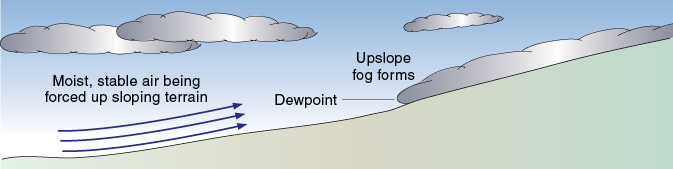

Upslope Fog

Moist air moving up a slope will cool adiabatically and, if it cools to below its dewpoint temperature, fog will form. This is known as upslope fog. It may form whether there is a cloud above or not. If the wind stops, the upslope fog will dissipate. Upslope fog is common on the eastern slopes of the Rockies and the Appalachian mountains.

Figure 18-6 Upslope fog.

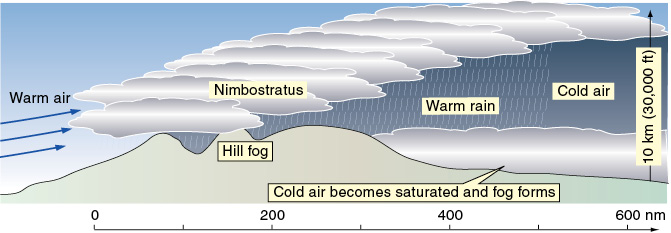

Frontal Fog

Frontal fog forms from the interaction of two air masses in one of two ways:

- as clouds that extend down to the surface during the passage of the front (forming mainly over hills and consequently called hill fog); or

- as air becomes saturated by the evaporation from rain that has fallen, known as precipitation-induced fog.

These conditions may develop in the cold air ahead of a warm front (or an occluded front), the prefrontal fog possibly being widespread.

Rain or drizzle falling from relatively warm air into cooler air may saturate it, forming precipitation-induced fog which may be thick and long-lasting over quite wide areas. Precipitation-induced fog is most likely to be associated with a warm front, but it can also be associated with a stationary front or a slow-moving cold front.

Figure 18-7 Fog associated with a warm front.

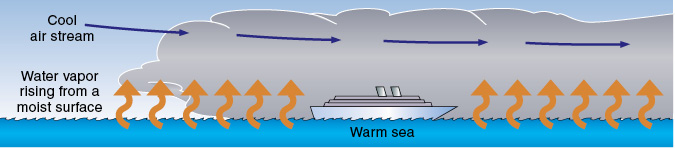

Steam Fog

Steam fog can form when cool air blows over a warm, moist surface (a warm sea or wet land), cooling the water vapor rising from the moist surface to below its dewpoint temperature and thereby causing fog. Steam fog over polar oceans is sometimes called Arctic sea smoke. It forms in air more than 10°C colder than water, and can be thick and widespread, causing serious visibility problems for ships. While flying in the Arctic, you will find very thick sea-smoke fog in the proximity of “leads” in polar ice where the ice sheet has cracked, exposing liquid water to the air.

Figure 18-8 Light turbulence and a risk of icing can be present in steam fog.

Review 18

Visibility

1. Poor visibility is more likely to result with:

a. stable air.

b. unstable air.

2. For an inversion to exist, temperature must:

a. increase with altitude.

b. decrease with altitude.

3. Does air and the particles it contains tend to rise through an inversion?

4. Does the presence of an inversion increase the risk of poor visibility?

5. What happens to the air beneath an inversion?

6. Describe the likely flying conditions and visibility beneath a low-level inversion.

7. How much mixing of the air occurs above and below an inversion?

8. Is there a risk of windshear to an airplane climbing or descending through an inversion?

9. What does the amount of water vapor that a parcel of air can hold largely depend on?

10. Can warm air hold more water vapor than cold air?

11. Is water vapor visible?

12. Are the water droplets formed when water vapor condenses out of cooling air visible?

13. As a parcel of air is cooled, is it capable of holding more water vapor?

14. What is the temperature to which a parcel of air must be cooled for it to become saturated called?

15. When will water vapor condense out of air? What effect does the presence of condensation nuclei in the air have on this process?

16. When do clouds, fog, dew, or frost form?

17. When does fog form?

18. What increases the possibility of fog in industrial areas?

19. What is a mixture of smoke and fog known as?

20. In which conditions is radiation fog most likely to form?

21. Is radiation fog more likely to form over land or over the sea?

22. Does land cool faster than the sea at night?

23. How is a common type of surface-based inversion that can lead to ground fog caused?

24. Describe the conditions in which dew forms.

25. Describe the conditions in which frost forms.

26. Describe the conditions in which advection fog is formed.

27. When and where is advection fog most likely?

28. Is wind necessary for advection fog to form?

29. What is moist air flowing over a cold surface likely to form?

30. Advection fog may form on the lee side of a large lake, the side to which the wind is blowing, in what conditions?

31. What wind strength is necessary for advection fog to be lifted in order to form low stratus clouds?

32. Moist, stable air being moved over gradually rising ground by a wind may lead to the formation of which type of fog?

33. What type(s) of fog depend on a wind in order to exist?

34. Can fog be dissipated by heating of the air?

35. Can haze layers be dissipated by heating of the air?

36. How can haze be dissipated?