LESSON 12

Flight Planning

“You got to be careful if you don’t know where you’re going, because you might not get there.” — attributed to Yogi Berra

This lesson will give you the opportunity to apply all of the information you have learned from the rest of the book in a practical form. With your knowledge of performance charts, weather, regulations, navigational charts, publications, and the airspace system, you should be able to plan a cross-country flight that is within the capability of your airplane, while complying with the regulations at all times.

Flight planning is in a state of flux in 2016; FAA Form 7233-1, the flight plan form we have been using for decades, will not be used after September. At that time, an ICAO-format flight plan will become mandatory for filing both VFR and IFR flight plans. The ICAO format has been used in Europe for many years, mostly by airlines.

But wait…do you need to file a flight plan, or is a request for radar flight following sufficient? Each has its benefits and drawbacks. First, filing a flight plan ensures that if you fail to arrive at your destination, the search-and-rescue (SAR) folks will roar into action (more later on SAR alerts). Of course, they will be searching along the route of flight that you filed, so if you decide to make a diversion without informing FSS the searchers will be looking in the wrong place. Then there is the perceived burden of having to close your flight plan upon arrival; yet failure to do so will activate the SAR folks and they will be really unhappy with you (more on that later, too).

For decades, VFR flight plans were not seen by air traffic controllers but were kept within the Flight Service Station system. With the implementation of International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) flight planning, ATC will have access to your flight plan if necessary; you are still not required to communicate with ATC unless you request flight following or enter Class B, C, or D airspace. If you fail to file a flight plan, of course, the talking heads on the evening news will assume that anything that happens during the flight is your fault.

Note: If you fly in the vicinity of our nation’s capitol or even plan a flight that will pass near it, you need to read 14 CFR §91.161. The flight plan required by that regulation is not for search and rescue but is for national security reasons. Failure to comply means that you will be mentioned on the six o’clock news.

Is flight following an acceptable substitute? You will be talking to a controller who knows exactly where your airplane is and who can react immediately if you encounter trouble of any kind…that’s a plus. But flight following is a workload-permitting activity for the ATC folks, and they can say “Radar services terminated, squawk VFR” at any time without any recourse on your part (which means that you have to know exactly where your airplane is at all times). If you request minimum safe altitude warnings the controller will give you a safety alert if your flight path will take you into something hard and unyielding; filing a flight plan does not give you this protection. When receiving radar services you will be ushered through Class C and Class D airspace (and TFRs) with no effort on your part—that’s another plus—and you will be warned if your flight path will take you into Class B airspace (in which case you say “Request clearance through the Class B”).

A word of caution: Statistics show that a significant number of pilots continue to fly into deteriorating weather or overfly refueling facilities with the gauges bouncing on empty because of “Plan Continuation Bias.” This fancy term means that they are so fixated on making it to their destinations without stopping that they overlook obvious hazards. This is a form of “get-home-itis” that applies to all flights. I can’t get inside of your head, I can only ask that you think clearly and realize that not getting to your destination is not the end of the world, but trying to get there in marginal weather or without a fuel stop might be the end of your world.

As you plan a cross-country flight, you know that the ability to maneuver in three dimensions makes you responsible for being aware at all times of your position, both geographic and vertical. You must ensure that you are always in compliance with the airspace regulations. These regulations are intended to keep airplanes safely separated and, in the case of VFR pilots, to provide minimum visibility and cloud clearance distances so that conflicting traffic can be seen in time for corrective action to be taken. “See and be seen” is the basis of safe operations in the National Airspace System. (See Chapter 9.)

Flight Planning and Flight Logs

As part of your practical test for the private pilot certificate, the examiner will expect you to provide a flight log for a cross-country flight; the Practical Test Standard calls for “a pre-planned VFR cross-country flight as previously assigned by the examiner,” so be sure to check with the examiner before checkride day. Note this important distinction: A flight plan is submitted to the FAA for search-and-rescue purposes; a flight log is where you document the proposed flight for your own reference in staying on course and calculating fuel consumption. You will use the results of your flight log calculations to fill in the flight plan form. The examiner will want to see both.

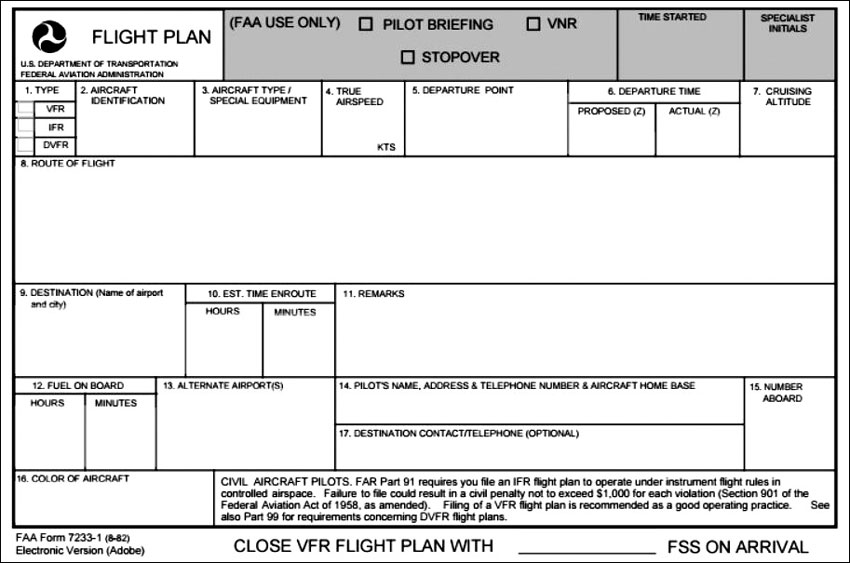

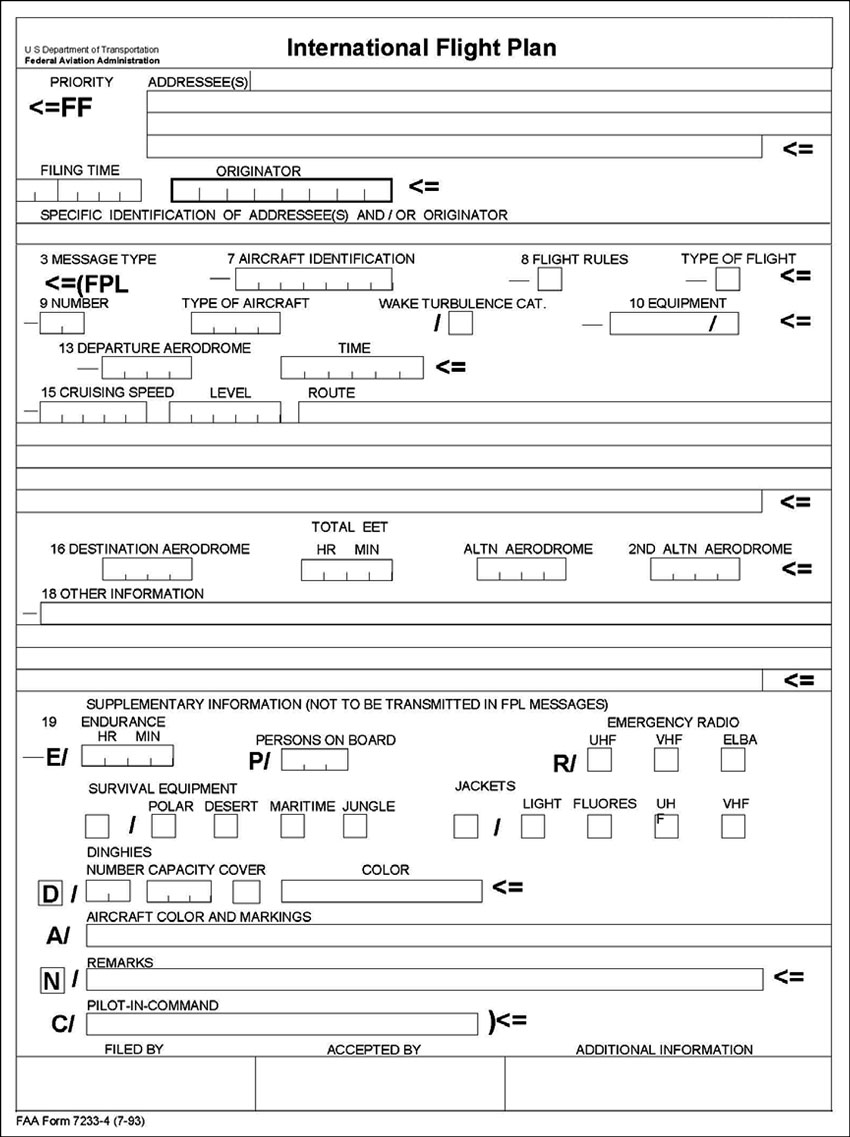

The FAA expects each applicant to use the flight planning method that he or she will use after becoming certificated, which in the 21st century seems to be a computer-generated plan from one of the many sources available. If you are an old-school applicant, you will do your flight planning manually and prepare a form such as Figure 12-1, the FAA form that will not be used after September 2016. This is a labor-intensive form, to be filled out manually and read to a Flight Service Station briefer. Or you might want to change over to the new ICAO-based FAA Form 7233-4, Figure 12-2. This is also labor-intensive for the same reasons. Details on how these forms are to be filled out can be found in AIM 5-1-8 and 5-1-9. There are easier ways to accomplish the tasks of preparing a flight log and filing a flight plan, as you will see later.

Figure 12-1. FAA Form 7233-1, going away in 2016.

Figure 12-2. New Form 7233-4, FAA International Flight Plan—the ICAO-based format.

Planning a flight is a four-step process: Getting a weather briefing, choosing a route and altitude, preparing a flight log based on the first two steps, and filing the flight plan.

Modern technology has made the tools for flight logs in Lesson 9 obsolescent except as backups to digital devices. Do a search for flight planning tools and you will find that there are several, and that most are free. Investigate www.fltplan.com, www.duats.com, and www.1800wxbrief.com as examples. In each case, you fill out a flight plan form online with the designators for the departure and destination airports and an initial altitude. These programs vary in detail, but the end result is a forecast-wind-corrected flight log. At the click of a mouse your flight plan is filed with the FSS.

If you choose to use a computerized flight planning program, expect the examiner to quiz you on how the various elements (winds, variation, true airspeed, deviation, etc.) are derived and what they mean. For now, we will do it the old-fashioned way just in case the examiner says, “How do you determine magnetic heading?”

Airplane:

4 seats, fixed gear

Gross weight 2,300 lbs, empty weight 1,364 lbs

150 HP, fixed-pitch propeller

Fuel capacity 38 gallons usable, 100LL

Oil 8 quarts not included in empty weight

2 navcomms, 360 channel comm, GPS

200 channel nav, transponder with Mode C

Pilot:

190 pounds

Passengers:

185 and 110 pounds

Note: The 110-lb passenger has shown up with a 200-pound friend who needs to get to Ellensburg to take a test tomorrow. Can you arrange the seating to stay inside the loading envelope? If the total weight exceeds the maximum allowable gross weight, will you be able to take off? If this is the case, how long will you have to fly at climb speed in order to burn off enough fuel to land safely if a return is required? If the unexpected passenger offers you $50, will this affect your decision?

The 110-pound passenger has never before flown in a light plane.

Baggage:

25 pounds; the unexpected passenger has 25 pounds of baggage. How will this affect your go/no-go decision?

Weight and Balance Calculation

|

Weight |

Moment |

|

|

Empty weight (from AFM) |

1,364 |

51.7 |

|

Fuel (usable) |

228 |

11.0 |

|

Baggage |

25 |

2.0 |

|

Oil (2 gal) |

15 |

-0.2 |

|

Pilot and 110-lb passenger |

300 |

11.2 |

|

Rear passenger |

185 |

13.5 |

|

Totals |

2,117 |

89.2 |

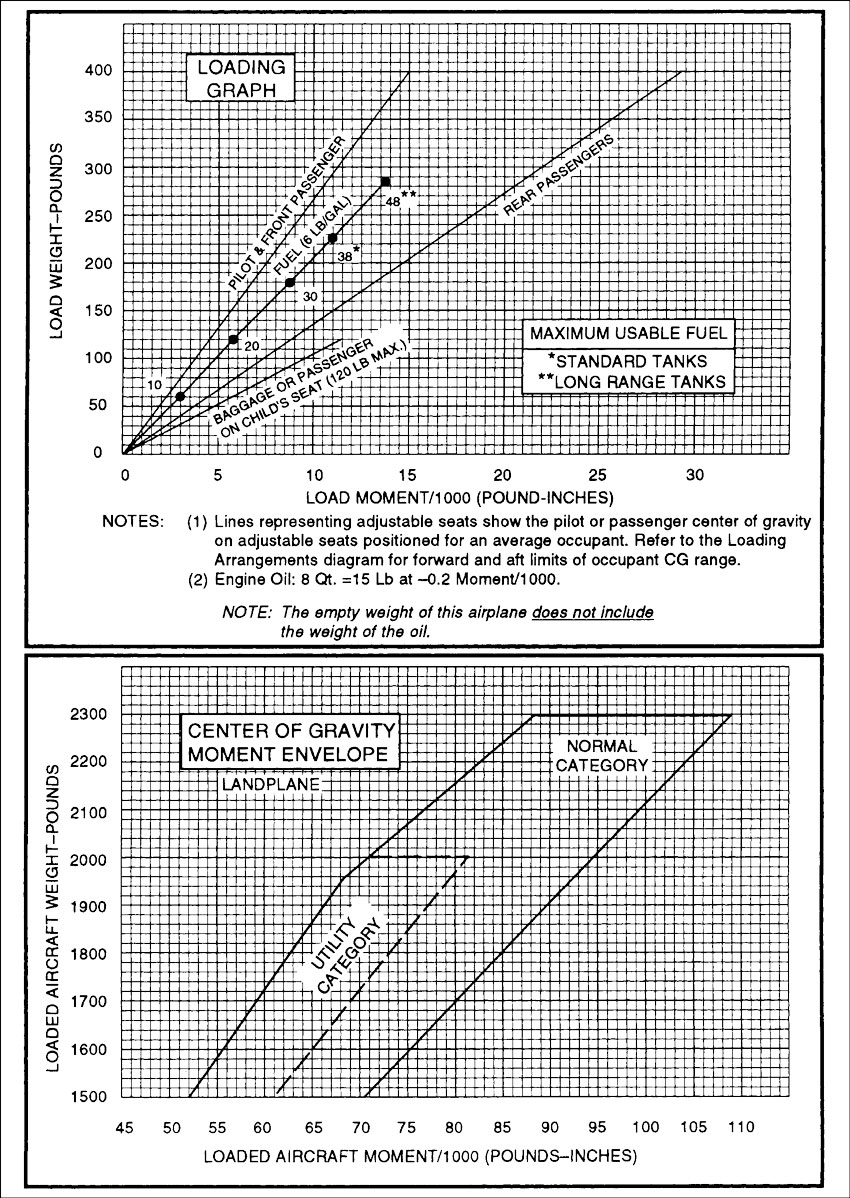

See Figure 12-3 for the Loading Graph and Center of Gravity Moment Envelope. Loading is within limits with most adverse weight distribution; moving the 110-pound passenger to the rear seat and the 185-pound passenger to the front seat would move the center of gravity forward. With these passengers and this fuel load you cannot mis-load the airplane.

Figure 12-3. Loading graph, CG moment envelope

Weather Briefing

Re-read Lesson 7 and self-brief as much as possible. When you call 1-800-wxbrief you should ask for a standard briefing if you have not received a previous briefing. An abbreviated briefing should be requested if you simply want to supplement information you already have or if you want to update one or two items: “I’ve been watching the weather channel and listening to my NOAA weather radio and it looks good for a VFR flight over the mountains; all I need is the terminal forecast for Yakima and the winds aloft at 12,000 feet.”

Ask for an outlook briefing if your departure time is more than six hours in the future: “I’m a VFR pilot and I’m planning a flight from Olympia to Ellensburg tomorrow. I’d like a (standard, abbreviated, outlook) weather briefing.” You should hear something like this:

“No hazardous weather is forecast for your route and time of flight. The synopsis is for a southwesterly flow aloft over Washington, caused by a stationary low at the surface and aloft 250 miles offshore from Vancouver Island. The air mass is somewhat unstable. At the surface, there is weak high pressure west of the Cascades. Freezing level is 8 thousand along the coast, sloping to 13 thousand at the eastern border.

“The Yakima terminal aerodrome forecast is calling for 10,000 broken until 1800Z then 7,000 scattered, wind 270° at 10 knots. Wenatchee is the same except the wind is forecast to be 320° at 10 knots. Olympia will remain essentially unchanged all day.

“The winds aloft for Seattle at 6,000 feet are forecast to be 220° at 13 knots, at 9,000 feet 210° at 21 knots.

“Restricted Area 6714 is active 13,000 feet and below. The threshold of runway 11 at Paine Field is displaced 1,100 feet eastward.”

If you want to know the status of Military Operating Areas or Military Training Routes, you will have to ask the briefer; this information will not be volunteered. Be sure to ask the briefer for NOTAMs (including published NOTAMs) that affect your flight. Be especially sure to ask about Temporary Flight Restrictions (the kind that dispatch fighter jets to make you land immediately). Also, it wouldn’t hurt to check for TFRs while in-flight to avoid nasty surprises.

Choosing a Route

An Example Flight: OLM to ELN

This flight will consist of both pilotage and electronic navigation. I have chosen a route using both in order to illustrate how describing a route by landmarks differs from the ICAO format that is now voluntary but will become mandatory in 2016. The route takes you from Olympia, Washington (KOLM) to Ellensburg, Washington (KELN), skirting restricted areas, dealing with Class B airspace, and flying over the Cascade Mountains. (Reference Appendix D for the full-color sectional excerpt showing this route drawn on the chart.)

Unless you plan to use radar flight following or make regular position reports, do not use round-robin flights outside of the training environment—file separate flight plans for each leg of the flight (AIM 6-2-7). The basic purpose for filing a VFR flight plan is to aid SAR forces if you fail to complete the flight. If you file a round-robin flight plan with a duration of five hours and run into trouble immediately after opening the flight plan with Flight Service, search efforts will not begin for five and one-half hours. That’s the best argument against round-robins. On this trip, you will stay in contact with ATC. With that in mind, filling out the flight plan form should be easy.

Note on the sectional chart excerpt (see Appendix D) that you cannot fly direct from OLM to ELN because of the restricted areas, so you need turning points that are easily visible…but the FSS computer will not accept proper names as waypoints so you need an alternative that is acceptable. That alternative is Fix-Radial-Distance (FRD), a nine-character group consisting of the three-letter identifier of the VORTAC, the radial from that VORTAC expressed as three digits, and the distance from the VORTAC, again expressed as three digits. SEA088024 is an example.

If you do not have a DME on board it does not make a bit of difference; if your turning point is 100 miles from the VORTAC it still doesn’t make any difference. If you don’t show up at your destination the search-and-rescue folks will be equipped to identify an FRD waypoint. All you want is something that the computer will accept.

An important part of preflight planning is reviewing your flight on the navigational chart to be sure that you are aware of any airspace restrictions, and that you know who to contact for any required clearances. You should also pick out easily identified ground speed checkpoints, and establish visual “brackets” on either side of your course and at the destination to insure that you do not wander too far off course or overfly the destination. (The bracketed text in the following flight planning paragraphs refer directly to points in the flight log illustrations.)

Planning Considerations, Olympia to Ellensburg

Olympia direct Ketron Island, which will be a visual checkpoint. Ketron Island is not named on either the terminal or sectional chart; it is the island directly west of Steilacoom—see Figure 12-4 to help locate this on the sectional. Overfly Nisqually Wildlife Refuge at least 2,000 feet AGL. Contact Seattle Approach Control on 121.1 Mhz as soon as possible and request flight following; that will smooth your passage over Gray Army Airfield and McChord AFB.

Figure 12-4. Ketron Island visual checkpoint.

On the flight plan form, file Ketron Island as TCM249006 (McChord VORTAC 249 radial at 6 NM) [Ketron] to avoid R-6703A. Ketron will appear in your flight log but not in your filed route. To further pin down your turning point, note that if you look to the north as you turn you will see Tacoma Narrows runway 35.

Pass north of McChord AFB above 3,000 feet MSL but below 5,000 to miss Seattle Class B airspace.

Over the northwest tip of Lake Tapps [Lake Tapps], maintain course to intercept V-2 4 NM northeast of Palmer (SEA088024 if you have DME); identify Palmer by the sand and gravel operation [Palmer] (see Figure 12-5).

Figure 12-5. Google Earth view of Palmer, WA.

From there via V-2 to Ellensburg; Palmer is four miles from V-2…your VOR needle should be moving toward the center as you approach the airway.

Military VFR route crosses V-2 near town of Lester (powerline also crosses beneath flightpath). Military flights will be below 1,500 feet AGL. Rights-of-way beneath high-tension lines are 100 to 200 feet wide and make excellent landmarks anywhere in the country.

Highest terrain within five miles of route is 5,750 feet MSL.

Ground speed checkpoints: McChord AFB to northwest tip of Lake Tapps 13 NM; 14 NM further to Palmer and V-2. (If you get as far as Chester Morse Lake you have flown through the airway.) Start timing when Hanson Reservoir dam [Hanson Dam] is off your right wing; next checkpoint is Easton State [Easton] at southern tip of Kachess Lake, 22 NM. Easton to Cle Elum is 13 NM, Cle Elum to ELN is 17 NM, and you should begin your descent to pattern altitude.

End bracket: Columbia River.

Frequencies: Olympia ground control and tower, Seattle Radio (open flight plan) Seattle Approach Control (advisories), Seattle and Ellensburg VORs, Seattle Center (flight following), ELN ASOS.

Which cruise altitude would you choose for crossing the mountains eastbound?

The hemispherical rule requires that you fly eastbound at an odd-thousand-plus 500 feet. The hemispherical rule does not apply within 3,000 feet of the surface, so 6,500 feet is a possible choice, but that altitude is only 1,000 feet above the ridges—and there is a southwest wind, which will create turbulence on the lee slopes. A ceiling of 6,000 feet at Stampede Pass means a cloud layer at approximately 9,800 feet, ruling out 9,500 feet as a cruise altitude. Choose 7,500 feet as your cruise altitude eastbound, and use 8,500 feet westbound.

Will you be able to see your checkpoints if the undercast does not burn off? How will you check your ground speed if this is the case? Abort or continue?

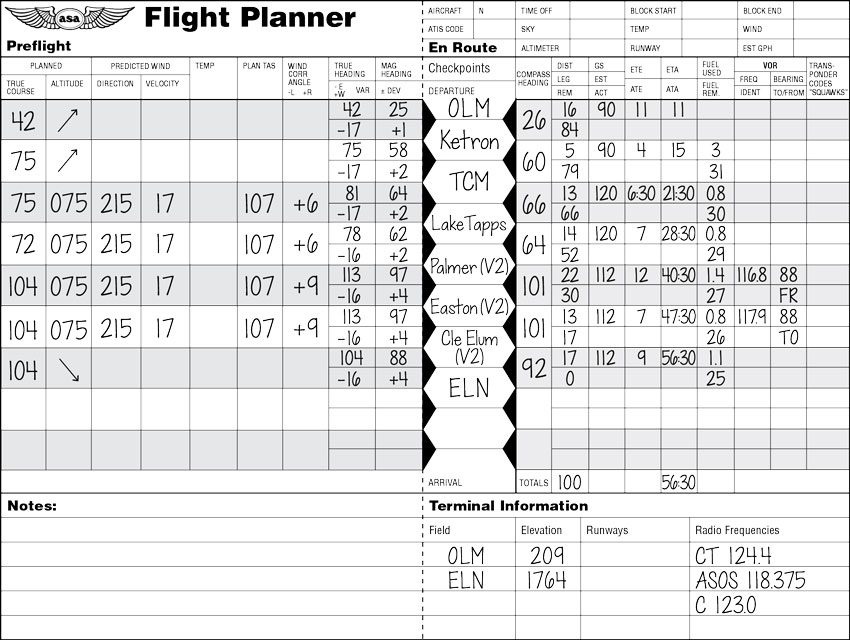

In preparing your flight log, you should record the result of your calculations, and not the individual elements. That is, you need to know the magnetic heading, but you do not need to record the true course, the magnetic variation, or the wind for in-flight use. (See the ASA Flight Planner, Figure 12-6.)

Figure 12-6. Flight planner, filled out.

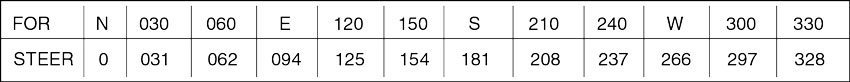

In addition (considering the built-in inaccuracy of the wind forecasts), computing and recording compass deviation and compass heading are unnecessary—although valuable for the FAA Knowledge Exam. If the heading indicator becomes inoperative, or of questionable accuracy, use your computed magnetic heading and the compass correction card to get compass course to steer. A compass correction card for the airplane you are using in this flight is provided here (Figure 12-7).

Figure 12-7. Compass correction card.

Eastbound, interpolate the wind at 7,500 feet from the winds aloft given by the briefer: 220°, 13 knots at 6,000 feet and 210°, 21 knots at 9,000 feet. This is how the magnetic heading and ground speed for the first leg is calculated, rounding off fractional results. The wind will have a greater effect during the relatively slow climb than when at cruise. Only the distance, magnetic heading, and ground speed figures from these calculations will appear in your flight log.

Note: Several flight computers, both manual and electronic, were used in making the heading and ground speed calculations for Figure 12-6. No two pilots will come up with the same answers.

Fuel Planning

Using the methods for finding time, speed, distance, and fuel burn, the climb from field elevation at Olympia (206 feet MSL) to the cruising altitude of 7,500 feet should take 15 minutes and consume 3 gallons of fuel (always round fuel consumption figures off to the next highest figure). You should have 31 gallons left at the top of the climb. Using the most conservative ground speed of 90 knots, you will be 23 miles into the trip with 83 miles to go when you reach cruise altitude. If you plan to descend at cruise speed (TAS 107) maintaining a ground speed of 112 knots, you will reach Ellensburg 44 minutes after leveling off, and will consume 6 gallons during that portion of the trip. You should have 25 gallons left when you arrive at Ellensburg.

Refuel at Ellensburg? You have rented the airplane “wet,” meaning that the FBO will reimburse you for any fuel you buy. But if you take the unexpected passenger and drop him off at ELN, the airplane will be 200 pounds (plus the fuel burned so far) lighter.

Any time you refuel en route, have the line person top-off the tanks, and divide the fuel pumped into the tanks by your flying time to see what the overall fuel burn was. (Stay with the airplane until you are sure that the correct grade of fuel is being pumped; line personnel have been known to make mistakes.) It should take about 13 gallons to top the tanks. If it takes more than 13 gallons, adjust your fuel burn estimate upward the next time you plan a flight in this airplane. Although it is legal to do so, never eat into your reserve fuel unless you are in an emergency situation and have advised ATC that you are declaring an emergency.

As your passengers deplane, what will they be thinking? “This guy is a nutcase, I’ll never fly in a light plane again,” or “I wonder how much it costs to learn to fly?” Your actions, your decision making, and your demeanor will affect their thinking.

Preparing the Flight Log

To continue with the flight planning process, here is a checklist of items that should be included in a flight log:

- The route of flight, with each leg identified by checkpoints or navigational aids. Note that because one of the reasons for filing a flight plan is to aid searchers if you do not show up at your destination, you want the flight plan form (not the flight log) to reflect that route: You can use “Over Lake Podunk” as a checkpoint in your flight log, but the FSS computer will not accept it as part of your route. More about this later in this lesson.

- The magnetic course between checkpoints. Your flight log need only show the heading, but the examiner may want to see how you converted the true course to a magnetic course using variation and deviation, and how you determined the wind correction angle (look back to Lesson 9).

- The distance between checkpoints in nautical miles.

- Your estimated ground speed for the leg. Again, do the calculations separately and put only the answer in the flight log, but expect to be asked how you made the calculations.

- Your estimated time between checkpoints, calculated by using the measured distance and estimated ground speed.

- Your estimate of the time you will pass over the next checkpoint. Leave this blank and update it in flight.

You will calculate “actual ground speed” when you measure the actual elapsed time between checkpoints and use the measured distance to solve the time-speed-distance problem. The only reason to write down the actual time between checkpoints is for when you and your instructor debrief after the trip is completed, but you should record the actual time over each checkpoint. I recommend that you write on the sectional chart itself rather than on the flight log—if you get disoriented you will be able to see the time at which you were over a known checkpoint. Then you can say, “Well, I was over Pine Lake ten minutes ago and I’m doing about a mile and a half a minute, so I must be within 15 miles of Pine Lake!”

Take advantage of technology and “fly” your planned route using Google Earth or the equivalent. Use the Airports page at www.1800wxbrief.com for a bird’s-eye view of your destination and enroute airports.

Those are the “bare bones” of a flight log. Have available an airport diagram for both the departure and destination airports, to facilitate ground operations. Keep track of the times when you change tanks on the flight log as well.

What will you do if deteriorating weather or a passenger emergency causes you to divert to an enroute airport? (You’d be surprised how many examiners have “heart attacks” or create similar distractions just when you thought everything was going smoothly.) “You have a sick passenger. What is the direction to the nearest airport, how long will it take you to get there, and how will you contact the authorities?” Your flight log should list alternate airports and their associated frequencies, just in case. Most online flight planning programs include this information. Learn to do an eyeball estimate of magnetic course using the compass rose around a convenient VOR symbol on the chart, and how to “guesstimate” distances at 8 miles to the inch—there won’t be time to measure courses and distances accurately when the examiner is pretending to be dying.

Remember—cross-country trips are the reason you wanted to learn to fly in the first place. Make them fun, but cover all the bases.

The foregoing will apply if you are a recreational pilot undertaking the additional training required in order for an instructor to lift the 50 NM restriction.

Look up the frequencies of radar facilities that can provide flight following, and write them on your flight planning form. Refer to the A/FD and the communications panel on sectional charts.

Remember that ground speed and wind correction angle calculations require true course, true airspeed, wind direction in relation to true north, and wind velocity. Keep in mind that the wind information you must rely on is a forecast and does not reflect reality. Magnetic variation on the sectional is almost certainly out of date, and the compass correction card in the cockpit is probably out of date.

Measure courses as accurately as possible using your flight plotter: this measurement is the only truly “accurate” element of flight planning, and its accuracy is based on your ability to read degrees from a protractor. True airspeed figures from the airplane’s performance chart were accurate when the airplane was new but its condition may no longer allow it to match the book figures. Plan conservatively—don’t expect book performance. I emphasize these points to keep you from thinking that precision is attainable.

Questions about cross-country planning on the knowledge exam will lead you to believe that pinpoint accuracy is possible; it is not. In real life, no two pilots assigned to plan the same flight will come up with identical answers…there are too many inaccuracies built into the system.

I strongly recommend that you get your true wind direction and velocity information from a Skew-T chart.

The forecast wind at cruise altitude is used for figuring ground speed and heading during climb: 90 knots is used as climb true airspeed and time to cruise altitude is based on a climb rate of 500 feet per minute. During the climb, fuel consumption is 9 gallons per hour, while in cruising flight only 7 gallons per hour are consumed. When you do your own fuel burn calculations for actual cross-country trips, always overestimate by rounding off the book figure to the next highest gallons-per-hour figure. Your legal reserve for daytime VFR is 30 minutes at cruise power, so you can’t touch 3.5 gallons. Accordingly, assume that only 34 gallons are available for use during this trip. Remember what I said in Lesson 9—treat wind forecasts with suspicion; assume that headwinds are stronger than forecast and tailwinds are weaker. This trip assumes that the forecasts are right on the button.

You will need clearance to transit Seattle Class B airspace (read “Plan B”, below); top of the Class B airspace is 10,000 feet MSL. You must hear “Cleared to operate in Seattle Class B airspace” from Approach Control; getting a radar vector is not a substitute for a clearance.

Filing the Flight Plan

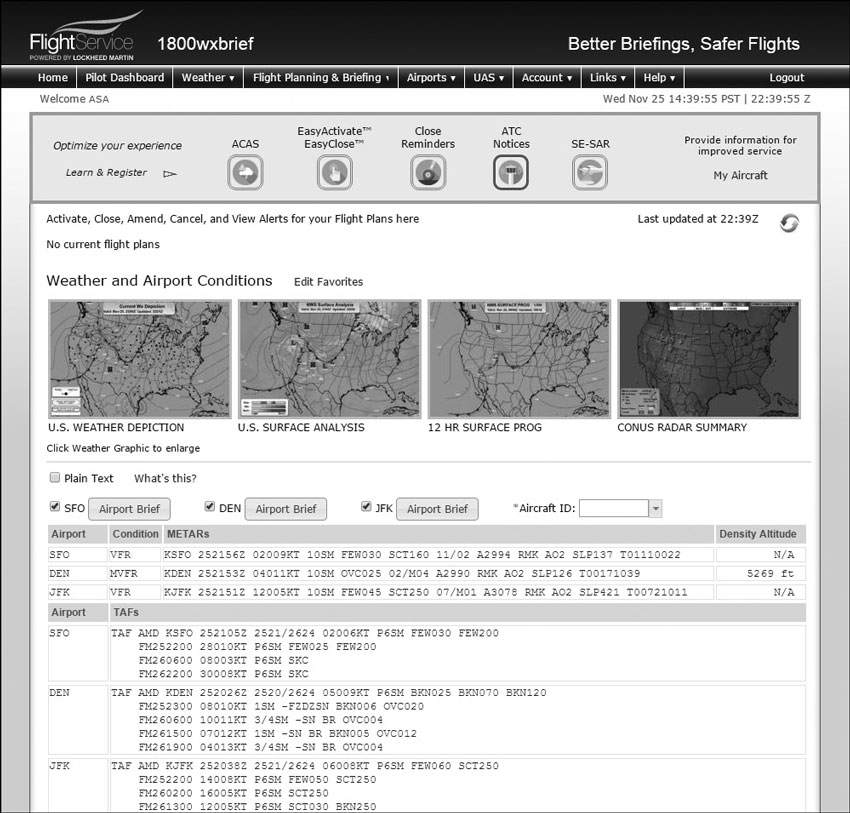

Your points of entry into the Flight Service Station network are by phone at 1-800-wxbrief or online at www.weatherbrief.com, www.duats.com, www.fltplan.com or a similar online flight planning program. My preference is to work directly with FSS. When you go to the website, register; it makes everything easier. There are some FSS products that are available without registering (weather and airport information) but why short-change yourself? There is a wealth of information and valuable services on this site, and I am going to suggest strongly that you make the FSS website your home page for flight planning. You might like DUATS or FltPlan better...you are the PIC.

Get started by going to www.1800wxbrief.com—again, being registered opens the door to many pilot services. The first page you will see when you log in as a registered user is Figure 12-8, the “Dashboard.” Accessing the services on the Dashboard requires that you be able to receive text messages. If this is not the case, click on the Flight Plans and Briefings at the top.

Figure 12-8. Flight plan “dashboard.”

The first Dashboard button is ACAS: The ACAS service will send alert messages to the Position Reporting and Communications Devices, Text Message Phone Numbers, and Email Addresses you select below, when adverse conditions arise along your planned route of flight. This service includes options for preflight and inflight alerting.

The second button is the EasyActivate™ and EasyClose™ service, which will send messages to the Text Message Phone Numbers and Email Addresses you select, with links for fast flight plan activation and closure.

Need a reminder? The Flight Plan Close Reminders service (third button) will send messages to the Position Reporting and Communications Devices, Text Message Phone Numbers, and Email Addresses you select, if your flight plan has not been closed at 20 minutes after the Estimated Time of Arrival.

The fourth button is the ATC Notices service, which will send messages to the Email Addresses you select when any of these events occurs:

a. Your filed flight plan has been accepted by ATC.

b. An ATC change to your flight plan’s route is detected.

Note: Service available for IFR, MIFR, and YFR flight rules.

Button five could be the most important: For flights within the Lockheed Martin Flight Service area (CONUS, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, and Guam), the SE-SAR service will monitor your position reports sent by the service providers of the Position Reporting and Communications Devices you select. When no movement is detected or when an emergency signal is received, this service will initiate SAR operations and send alert messages to the Position Reporting and Communications Devices, Text Message Phone Numbers, and Email Addresses you select.

Whether you use the Dashboard or not, the next step is to click on the Flight Plans and Briefings tab and select Flight Plans from the menu; then click on ICAO. As mentioned, the old familiar FAA flight plan form that has been used for decades will go away in late 2016, so get used to ICAO right now.

The ICAO Way

Go to www.1800wxbrief.com and log in. The weather tab is self-explanatory. Click on the Flight Planning and Briefing tab, then select Briefings, Flight Plans, and Navlogs from the drop-down menu. Click on the ICAO tab, and you will see the flight plan form (see Appendix D for an example of the ICAO form).

Note the magnifying glass icons adjacent to several of the items. Where an item requires that you choose among many options, clicking on the icon returns a drop-down menu so that you need not look anything up.

For help in filling out the flight plan form click on “User Guide” under the Help tab. This is how I filed the OLM-ELN flight:

Aircraft ID: N1357X

Flight Rule: VFR

Flight Type: G (General aviation)

No. of Aircraft: N/A

Aircraft Type: C172 (use drop-down menu)

Wake Turbulence: L (for light)

Aircraft Equipment: SG (S for Standard Comm/Nav; G for GPS…keep it simple.)

Departure: KOLM

Departure Time and Date: MM/DD/YYYY 1200 PDT

Cruising Speed: N0112 (N = knots, 4 digits for speed)

Level: A075 (A = altitude in hundreds of feet)

Surveillance Equipment: C (Mode C transponder)

Route of Flight: OLM TCM249006 SEA088024 ELN (The fix-radial-distance waypoints are needed for the ATC computer; your flight log will include visual checkpoints in the same locations.)

Destination: KELN

Total Estimated Elapsed Time: 0055

Fuel Endurance: 0400

Persons on Board: 3

Aircraft Color and Markings: W/BK/R

A click of the File button and you are in the system. If there is anything questionable about your filing, an error message will pop up pointing out what needs to be corrected.

Flying the Planned Trip

Follow along on the full-color sectional chart excerpts in Appendix D.

After leaving the Olympia Class D airspace, climb as rapidly as possible to pass over wildlife refuge at a height of at least 2,000 feet AGL. Open the VFR flight plan with Seattle Radio on 122.2 (the common FSS frequency). Look ahead to identify Ketron Island just off of the mainland; looking north as you turn at Ketron, you will see Tacoma Narrows Airport’s runway 35—another visual verification of your position.

Contact Seattle Approach Control on 121.1 (the frequency is in the A/FD) for traffic advisories. No clearance required for Gray AAF or McChord AFB Class D airspace if above 2,800 feet msl, but that is too close to the floor of Class B airspace—better talk to the towers. After passing Ketron (start time for ground speed check), steer toward Lake Tapps; call Seattle Approach for clearance into Class B airspace before reaching 3,000 feet.

Check time at northwest tip of Lake Tapps and compute ground speed. Estimate time of arrival at Palmer. Tune #1 VOR receiver to Seattle frequency and identify. Set omni-bearing selector to 088°. Note a railroad to the right of V-2 passes through Palmer…note the sand and gravel pit. As VOR course deviation needle centers, turn to follow V-2. If you see Chester Morse Lake ahead, you have flown through the airway.

The undercast has obscured all of your visual checkpoints until you get to Palmer; your fuel burn so far is an educated guess. Abort or continue? There is an emergency airfield at Easton, and Cle Elum is just on the other side of the mountains... Abort or continue?

The airway roughly parallels Interstate 90 and offers good visual checkpoints: three lakes, plus Cle Elum and De Vere airports. Ellensburg is uncontrolled; use 123.0 for position reports.

Plan B

The trip that you have just planned and for which you have prepared a flight log assumes that you will receive clearance into the Seattle Class B airspace upon request. But what if you are told “unable”? That is when you need a backup plan that you can put into action without a blizzard of paperwork in the cockpit. This is true whether you encounter the Class B airspace shortly after takeoff, as in our imaginary trip, or while en route.

Almost all of the airports associated with Class B airspace have VFR flyways, corridors, transition routes, or Special Flight Rules Areas, and it is your job to read everything about them on their Terminal Area Charts. For pilots based near or flying through the Washington, DC area, 14 CFR §91.161 must be complied with. In most cases, the VFR routes are printed on the back of the TAC; sometimes they are inserts on the front of the chart. For some, communication with ATC must be established before entering the VFR route, while others require only that you monitor 122.750. In any case, developing a Plan B is part of the flight planning process.

While sitting in the pilot’s lounge at Olympia airport and looking at the sectional chart, you can see that diverting to the northeast to stay below the 5000 foot floor of the Seattle Class B takes you toward restricted areas and the Class D airspace belonging to the two military airfields. Do you feel comfortable with that? Would you check the status of the restricted areas with your FSS briefer?

How about going north toward Port Orchard (airport E on the sectional excerpt), remaining between 1,500› and 2,000›, using the VFR transition route to fly over Seattle-Tacoma International, and then outbound on V-2? Takes longer but requires less hassle, except for getting clearance from the SEA tower. There is no correct answer to these questions; you must decide which Plan B you will put into play, turn toward the diversion route, notify FSS of your change in route, and give them your best guess as to a revised ETA at Ellensburg.

What happens to your carefully prepared flight log? Remember that you had two reasons for doing it: (1) to evaluate your planned route for terrain, man-made obstructions, and special use airspace and provide a line on the chart for following that route; and (2) to calculate fuel consumption using forecast winds and book performance figures to ensure that you have enough fuel to reach your destination with VFR reserves. Understand that you do not have to land with your reserve fuel intact—but you must have sufficient fuel at takeoff to meet the reserve requirement. Too many pilots use this as an excuse to stretch their fuel supply and end up in the trees or weeds. Also understand that the winds will probably not be what was forecast and that it is unlikely that your airplane will deliver book performance.

So your flight log no longer describes your actual route of flight…so what? Follow your Plan B and insert an enroute fuel stop, if your original plan envisioned a non-stop flight. On your trip from Olympia to Ellensburg, you are back on track when you reach the point where your Plan A route intercepted V-2. Your altitude is probable not what you had planned for, but if you climbed to stay with the Class B floors as they stepped up, you will be well clear of the terrain.

This whole Plan B discussion is meant to encourage you to think “What if…?” Your instructor might not agree with the alternatives that I have offered, but that is a good thing. If you fly in areas where you might encounter Class B airspace, this mental exercise will pay off.

Where Do We Go From Here?

As I write this in 2016, a pilot is deemed ready for his or her checkride when the minimum flight experience dictated by the regulations have been logged and their instructor is satisfied that the maneuvers called out in the Practical Test Standard (or Airman Certification Standard, when it becomes effective) will be performed within the allowed tolerances. Also, the applicant will be required to “exhibit satisfactory knowledge, skills, and risk management” applicable to the maneuvers and procedures demonstrated. This is a major expansion of what a pilot needs to know.

The goal of the FAA-Industry-Training Standards Program is to change the way pilots are evaluated toward a scenario-based method. This means that instead of flawlessly executing S Turns Across a Road (for example), an applicant will be required to take off on a cross-country trip and demonstrate situational awareness, good decision-making skills, deal with failures and unusual situations, and exhibit mastery of the technology in the cockpit. Obviously this change in training methods reflects the growing number of sophisticated trainers that meet the definition of Technically Advanced Aircraft. There is no timetable for this change, it will be incremental.

I encourage you to read the aviation press to keep up with the changes, and also to join in one or more of the many online pilot forums—you will find yourself exchanging ideas, questions, and experiences with pilots at all levels in the industry.

Blue Skies and Tailwinds!!!