17

Wind, Air Masses, and Fronts

The Nature of the Atmosphere

The earth is surrounded by a mixture of gases which are held to it by gravity. The mixture of gases is called air, and the space it occupies is called the atmosphere. The atmosphere is important to pilots because it is the medium in which we fly.

Air density and air pressure decrease with altitude. Temperature also decreases with altitude, until a certain level in the atmosphere known as the tropopause, above which the temperature does not vary much. Another way of saying this is that at the tropopause the temperature lapse rate changes abruptly.

The space between the earth’s surface and the tropopause is called the troposphere, and it is in this part of the atmosphere that most of the water vapor is contained, and where most of the vertical movement of air and the creation of “weather” (clouds) occurs. Unstable air, if forced aloft, will tend to keep rising and possibly cause cumuliform clouds. Stable air, if forced aloft, will tend to stop rising and possibly form stratiform clouds. The term “wind” refers to the flow of air over the earth’s surface. This flow is almost completely horizontal, with only about 1⁄1,000 of the total flow being vertical.

The tropopause is approximately 65,000 feet above the equator, and descends in steps to approximately 20,000 feet over the poles. Jet stream tubes of winds 50 knots or greater can form along the breaks. The average altitude of the tropopause in mid-latitudes is about 37,000 feet. The part of the atmosphere directly above the tropopause is called the stratosphere, and high-flying jets often cruise up there. It experiences little change in temperature or vertical movement of air, contains little moisture, and so there is an absence of clouds.

Figure 17-1 The tropopause, where jet streams and clear air turbulence can occur.

The Cause of Weather

The primary cause of weather is uneven heating of different areas of the earth by the sun. The warmer air is less dense and tends to rise, causing pressure changes, and so circulation of the air begins.

Winds

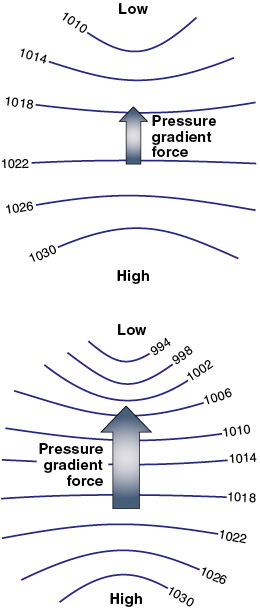

On weather charts, places of equal pressure are joined with lines called isobars. Air will tend to flow into the lower pressure areas (resulting from the warm air rising) from the higher pressure areas. The greater the pressure gradient, the closer the isobars are together, the greater the pressure gradient force causing winds to start blowing across the isobars.

Figure 17-2 The pressure gradient force will start a parcel of air moving.

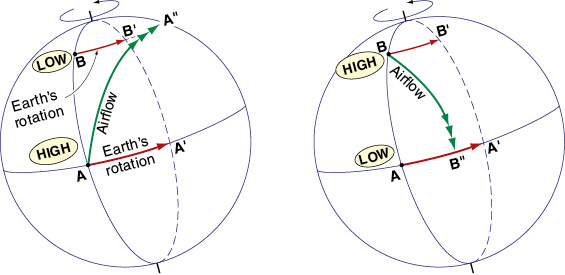

The wind that initially moves across the isobars is caused to turn right (in the Northern Hemisphere) by the Coriolis force. The Coriolis force acts on a moving parcel of air. It is not a real force, but an apparent force resulting from the passage of the air over the rotating earth.

Imagine a parcel of air that is stationary over point A on the equator (see figure 17-3). It is in fact moving with point A as the earth rotates on its axis from west to east. Now, suppose that a pressure gradient exists with a high pressure at A and a low pressure at point B, directly north of A. The parcel of air at A starts moving toward B, but still with its motion toward the east due to the earth’s rotation.

Figure 17-3 The Coriolis force acts towards the right in the Northern Hemisphere.

The further north one goes away from the equator, the less is this easterly motion of the earth, and so the earth will lag behind the easterly motion of the parcel of air. Point B will only have moved to B', but the parcel of air will have moved to A". In other words, to an observer standing on the earth’s surface the parcel of air will appear to turn to the right. This effect is caused by the Coriolis force.

If the parcel of air was being accelerated in a southerly direction from a high pressure area in the Northern Hemisphere toward a low near the equator, the earth’s rotation toward the east would “get away from it” and so the air flow would appear to turn right also — A having moved to A', but the airflow having only reached B' to the west.

The faster the airflow, the greater the wind speed, the greater the Coriolis effect — if there is no air flow, then there is no Coriolis effect. The Coriolis effect is also greater in regions away from the equator and toward the poles, where changes in latitude cause more significant changes in the speed at which each point is moving toward the east.

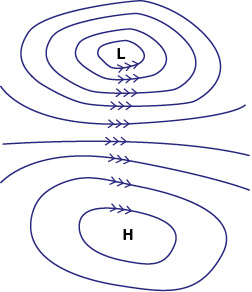

In the Northern Hemisphere, the Coriolis force deflects the winds to the right, until the Coriolis force balances the pressure gradient force, resulting in the geostrophic wind or the gradient wind that flows parallel to the curved isobars, clockwise around a high and counterclockwise around a low. (In the Southern Hemisphere, the situation is reversed and winds are deflected to the left.)

Figure 17-4 Winds flow clockwise around a high and counterclockwise around a low in the Northern Hemisphere.

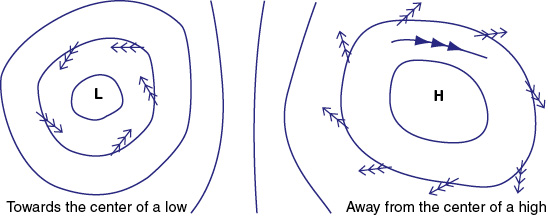

In the friction layer between about 2,000 feet AGL and the surface, friction slows the winds down — a lower wind speed means less Coriolis effect, and so winds, due to the friction effect reducing the wind speed, will tend to flow at an angle across the isobars toward the lower pressure.

Figure 17-5 Friction causes the surface winds to weaken in strength and flow across the isobars.

Windshear

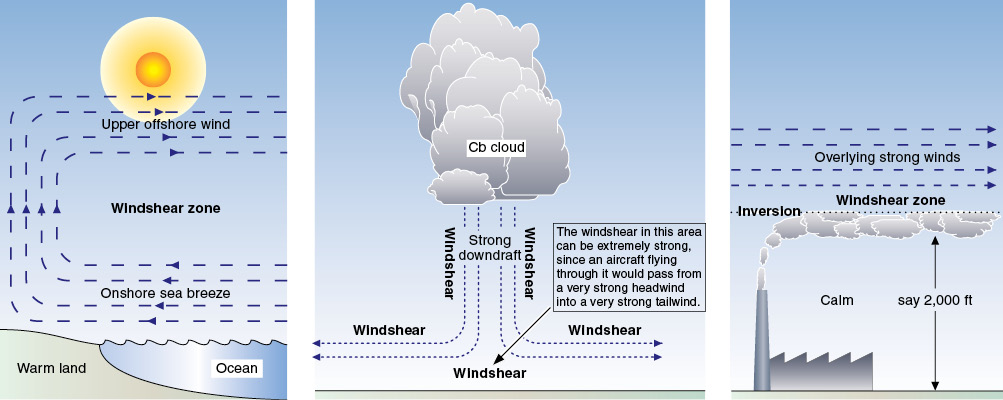

Windshear is the variation of wind speed and/or direction from place to place. It affects the flight path and airspeed of an airplane and can be a hazard to aviation.

Windshear is generally present to some extent as an airplane approaches the ground for a landing, because of the different speed and direction of the surface wind compared to the wind at altitude. Low-level windshear can be quite marked at night or in the early morning when there is little mixing of the layers, or when a temperature inversion exists.

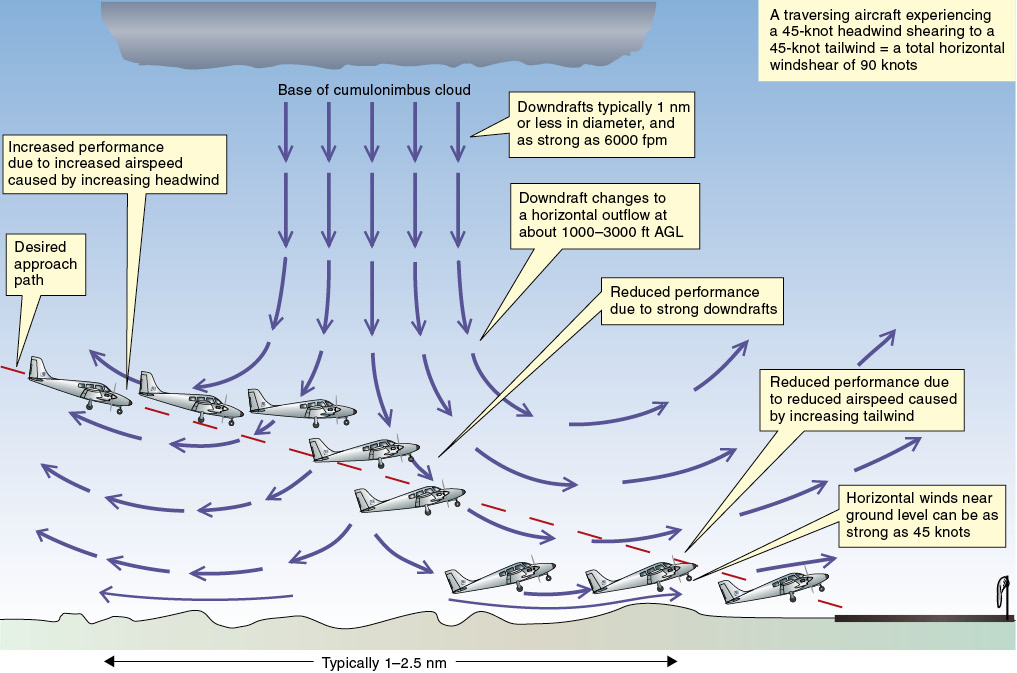

Windshear can also be expected when a sea breeze or a land breeze is blowing, or when in the vicinity of a thunderstorm. Cumulonimbus clouds have enormous updrafts and downdrafts associated with them, and the effects can be felt up to 10 or 20 NM away from the actual cloud. Windshear and turbulence associated with a thunderstorm can destroy an airplane.

Windshear often is present in the wind changes that occur around fronts, usually prior to the passage of a warm front, and during or just after the passage of a cold front. It is also likely to be present in the air surrounding a fast moving jet stream.

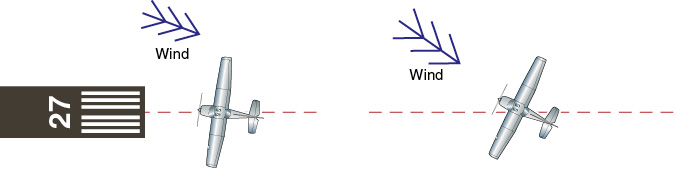

Figure 17-6 Windshear is a change of wind speed and/or direction between various places and altitudes.

Windshear on the Approach

An understanding of windshear helps explain why alterations of pitch attitude and/or power are continually required to maintain a desired flight path, just as changes in heading are required to maintain a steady course.

The study of windshear and its effect on airplanes, and what protective measures can be taken to avoid potentially dangerous results, is still in its infancy and much remains to be learned.

What is certain is that every airplane and every pilot will be affected by windshear — usually the light windshear that occurs in everyday flying, but occasionally a moderate windshear that requires positive recovery action from the pilot. On rare occasions, severe windshears can occur from which a recovery may even be impossible. A little knowledge can help you understand how to avoid significant windshear, and the best way to recover from inadvertent flight into areas affected by these conditions..

Windshear Terminology

A windshear is defined as a change in wind direction and/or wind speed in space. This includes updrafts, downdrafts, and lateral wind changes. Any change in the wind velocity (be it a change in speed or in direction) as you move from one point to another is a windshear. The stronger the change and the shorter the distance within which it occurs, the stronger the windshear.

- Updrafts and downdrafts are the vertical components of wind. The most hazardous updrafts and downdrafts are those associated with thunderstorms.

- The term low-level windshear is used to specify any windshear occurring along the final approach path prior to landing, along the runway and along the takeoff/initial climb-out flight path. Windshear near the ground (below about 3,000 feet) is often the most critical in terms of safety for the airplane. Windshear is quite common when there is a low-level temperature inversion.

- Turbulence is eddy motions in the atmosphere which vary both with time and from place to place.

The Effects of Windshear on Aircraft

Most of our studies have considered an airplane flying in a reasonably stable air mass which has a steady motion relative to the ground, in a steady wind situation. We have seen how an airplane climbing out in a steady headwind will have a better climb gradient over the ground compared to the tailwind situation, and how an airplane will glide further over the ground downwind, compared to into the wind.

An actual air mass does not move in a totally steady manner — there will be gusts and updrafts and changes of wind speed and direction, etc., which the airplane will encounter as it flies through the air mass. These windshears will have a transient effect on the flight path of an airplane.

An Example of Windshear

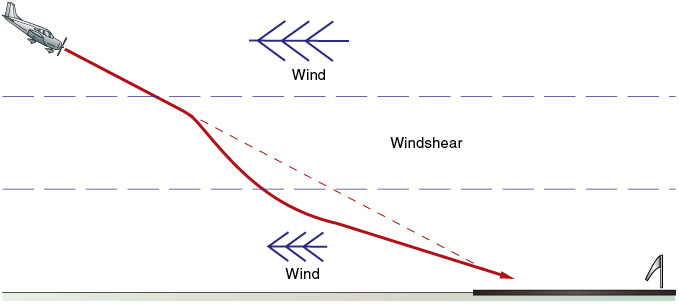

Even when the wind is relatively calm on the ground, it is not unusual for the light and variable surface wind to suddenly change into a strong and steady wind at a level only a few hundred feet above the ground. If we consider an airplane making an approach to land in these conditions, we can see the effect the windshear has as the airplane passes through the shear.

An airplane flying through the air has inertia which is resistant to change. This inertia depends on its mass and velocity relative to the ground. If the airplane has an airspeed of 80 knots and the headwind component is 30 knots, then the inertial speed of the airplane over the ground is (80 - 30) = 50 knots.

When the airplane flies down into the calm air, the headwind component reduces reasonably quickly to (let us say) 5 knots. The inertial speed of the airplane over the ground is still 50 knots, but the new headwind of only 5 knots will mean that its airspeed has suddenly dropped back to 55 KIAS.

The pilot will observe a sudden drop in indicated airspeed and a change in the performance of the airplane — at 55 KIAS the performance will be quite different to that available at 80 KIAS. The first indication of windshear to a pilot is usually a sudden change in indicated airspeed.

The normal reaction with a sudden loss of airspeed is to add power or to lower the nose to regain airspeed, and to avoid undershooting the desired flight path. The stronger the windshear, the greater the changes in power and attitude that will be required. Any fluctuations in wind will require adjustments by the pilot, and this is why you have to work so hard sometimes, especially when approaching to land.

Figure 17-7 A typical windshear situation — calm on the ground with a wind at altitude.

Windshear Effects on an Aircraft’s Flight Path

The effects of windshear on an airplane’s flight path depend on the nature and location of the shear.

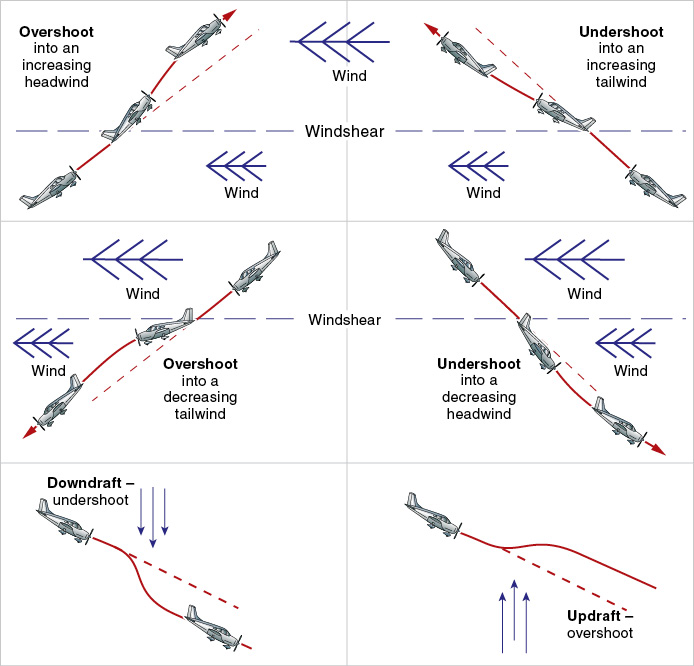

Overshoot Effect

Overshoot effect is caused by a windshear which results in the airplane flying above the desired flight path and/or an increase in indicated airspeed. The nose of the airplane may also tend to rise.

Overshoot effect may result from flying into an increasing headwind, a decreasing tailwind, from a tailwind into a headwind, or an updraft. Overshoot effect is sometimes referred to as a performance-increasing windshear, since it causes an increase in airspeed and/or altitude.

Undershoot Effect

Undershoot effect is caused by a windshear which results in an airplane flying below the desired flight path and/or a decrease in indicated airspeed. The nose of the airplane may also tend to drop.

Undershoot effect may result from flying into a decreasing headwind, an increasing tailwind, from a headwind into a tailwind, or into a downdraft. Undershoot effect is sometimes referred to as a performance-decreasing windshear, since it causes a loss of airspeed and/or altitude.

Figure 17-8 Six common windshear situations.

Note. The actual effect of a windshear depends on:

1. the nature of the windshear;

2. whether the airplane is climbing or descending through that particular windshear; and

3. in which direction the airplane is proceeding.

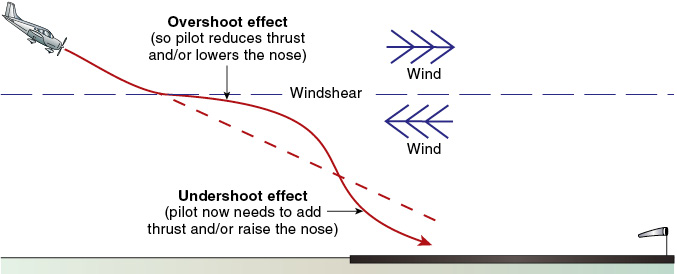

Windshear Reversal Effect

Windshear reversal effect is caused by a windshear which results in the initial effect on the airplane being reversed as the aircraft proceeds further along the flight path. It would be described as overshoot effect followed by undershoot, or undershoot followed by overshoot effect, as appropriate.

Windshear reversal effect is a common phenomenon that pilots often experience on approach to land, when things are usually happening too fast to analyze exactly what is taking place in terms of wind. The pilot can, of course, observe undershoot and overshoot effect and react accordingly with changes in attitude and/or power.

Lateral Windshear

Lateral windshear can result in a crosswind effect. This is caused by a windshear that requires a rapid change of aircraft heading in order to maintain a desired track (not uncommon in a crosswind approach and landing, because the crosswind component changes as the airplane nears the ground).

Figure 17-9 Windshear reversal effect.

Figure 17-10 Crosswind effect.

The Causes of Windshear

There are many causes of windshear. They include obstructions and terrain features which disrupt the normal smooth wind flow, localized vertical air movements associated with cumulonimbus (thunderstorms) and large cumulus clouds (gust fronts, downbursts and microbursts), low-level temperature inversions, sea breezes and jet streams.

The following phenomena are known to be strongly associated with the occurrence of windshear, and a pilot should exercise appropriate caution if any are observed, especially during takeoff and landing:

- roll clouds and/or dust raised ahead of an approaching squall line;

- strong, gusty surface winds at an airport with hills or large buildings located near the runway;

- windsocks on various parts of the airport indicating different winds (some airports are equipped with a low level windshear alert system (LLWAS), which is designed to detect such a situation, allowing ATC to provide advisory warnings to landing and departing aircraft);

- curling or ring-shaped dust clouds raised by downdrafts beneath a convective cloud (even if the ceiling is relatively high);

- virga associated with a convective cloud (rain falling from the base of the cloud and evaporating before reaching the ground causing a cold parcel of air which may descend rapidly); or

- thunderstorms.

Figure 17-11 Avoid thunderstorms.

In particular, we strongly recommend that all thunderstorms and cumulonimbus clouds be avoided. A strong downburst from the base of one of these clouds will spread out as it nears the ground. If an airplane encounters one of these on takeoff or landing, the initial effect may be an overshoot followed immediately by an extreme undershoot. You should delay the approach and hold in the vicinity until the storms move on, or divert. Takeoff should also be delayed.

Pilots are strongly encouraged to promptly report any windshear encounters. Windshear PIREPs will assist other pilots in avoiding windshear on takeoff and landing. Reports should always include a description of the effect of the shear on the airplane, such as “loss of 30 knots at 500 feet.”

As well as considering the potential for windshear on final approach to land, you should also think about the possibility of wake turbulence caused by the wingtip vortices from preceding aircraft (especially heavy aircraft flying slowly at high angles of attack).

If possible, stay above the flight path of a preceding heavy jet aircraft, and land beyond its touchdown point. Be especially cautious in light quartering tailwinds — the crosswind component can cause the upwind vortex to drift onto the runway and the tailwind component can drift the vortices into your touchdown zone.

Air Masses and Frontal Weather

Air Masses

An air mass is a large parcel of air with fairly consistent properties (such as temperature and moisture content) throughout. It is usual to classify an air mass according to:

- its origin;

- its path over the earth’s surface; and

- whether the air is diverging or converging.

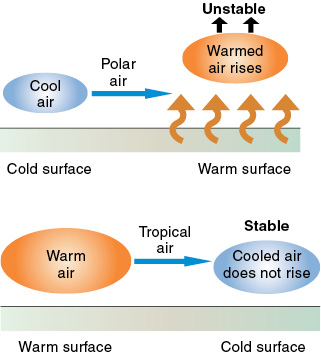

Figure 17-12 Polar air warms and becomes unstable (top) and tropical air cools and becomes stable (bottom).

The Origin of an Air Mass

Maritime air flowing over an ocean will absorb moisture and tend to become saturated in its lower levels; continental air flowing over a land mass will remain reasonably dry since little water is available for evaporation.

Air Mass Movement

The track of an air mass across the earth’s surface determines its characteristics. Polar air flowing toward the lower latitudes will be warmed from below and therefore will become unstable. Conversely, tropical air flowing to higher latitudes will be cooled from below and will become more stable.

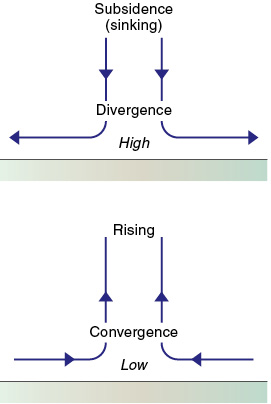

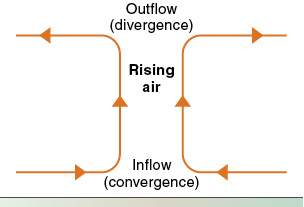

Divergence or Convergence

An air mass influenced by the divergence of air flowing out of a high pressure system at the earth’s surface will slowly sink (known as subsidence) and become warmer, drier and more stable. An air mass influenced by convergence as air flows into a low pressure system at the surface will be forced to rise slowly, becoming cooler, moister and less stable.

Figure 17-13 Subsiding air, resulting from divergence, is stable (top) and rising air, resulting from convergence, is unstable (bottom).

Frontal Weather

Air masses have different characteristics, depending on their origin and the type of surface over which they have been passing. Because of these differences there is usually a distinct division between adjacent air masses. These divisions are known as fronts, and there are two basic types — cold fronts and warm fronts. Frontal activity describes the interaction between the air masses, as one mass replaces the other. There is always a wind change when a front passes.

The Warm Front

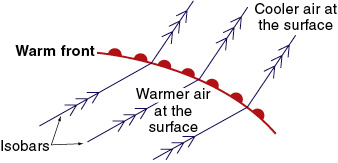

If two air masses meet so that the warmer air replaces the cooler air at the surface, a warm front is said to exist. The boundary at the earth’s surface between the two air masses is represented on a weather chart as a line with semicircles pointed in the direction of movement.

Figure 17-14 Depiction of a warm front on a weather chart.

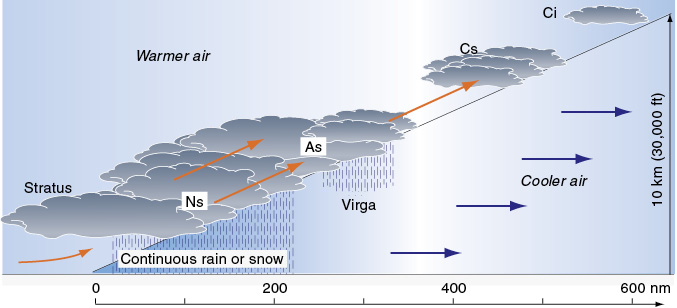

The slope formed in a warm front as the warm air slides up over the cold air is fairly shallow. Therefore the clouds that form in the (usually quite stable) rising warm air are likely to be stratiform. In a warm front, the frontal air at altitude is actually well ahead of the line as depicted on the weather chart. The cirrus could be some 600 NM ahead of the surface front, and rain could be falling up to approximately 200 NM ahead of it. The slope of the warm front is typically 1 in 150, much flatter than a cold front, and has been exaggerated in the diagram (figure 17-15).

Figure 17-15 Cross-section of a warm front.

The Warm Front from the Ground

As a warm front gradually passes, an observer on the ground may first see high cirrus clouds, which will slowly be followed by a lowering base of cirrostratus, altostratus and nimbostratus. Rain may be falling from the altostratus and possibly evaporating before it reaches the ground, virga, and from the nimbostratus. The rain from the nimbostratus may be continuous until the warm front passes and may, due to its evaporation, cause fog. Also, the visibility may be quite poor.

Figure 17-16 Altostratus.

Figure 17-17 Nimbostratus indicating heavy or saturated air.

The atmospheric pressure usually falls continuously as the warm front approaches and, as it passes, either stop falling or falls at a lower rate. The air temperature rises as the warm air moves in over the surface. The warm air holds more moisture than the cold air, and the dewpoint temperature in the warmer air is higher.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the wind direction will veer (a clockwise change of direction) as the warm front passes (there is a counterclockwise change of direction in the Southern Hemisphere). Behind the warm front, and after it passes, there are likely to be stratus clouds. Visibility may still be poor. Weather associated with a warm front may extend over several hundred miles.

The general characteristics of a warm front are:

- lowering stratiform clouds;

- increasing rain, with the possibility of poor visibility and fog;

- possible low-level windshear before the warm front passes;

- falling atmospheric pressure that slows down or stops;

- wind that veers (clockwise change of direction); and

- rising temperature.

The Warm Front from the Air

What a pilot sees, and in which order it is seen, will depend on the direction of flight. If the pilot is flying toward the warm front, in the cold sector underneath the warm air, he or she may see a gradually lowering cloud base with steady rain falling.

Figure 17-18 Warm, moist air and cloud.

If the airplane is at subzero temperatures, the rain may freeze and form ice on the wings, thereby decreasing their aerodynamic qualities. The clouds may be as low as ground level (hill fog) and sometimes the lower layers of stratiform clouds can conceal cumulonimbus and thunderstorm activity. Visibility may be quite poor.

There will be a wind change either side of the front and a change of heading may be required to maintain course.

The Cold Front

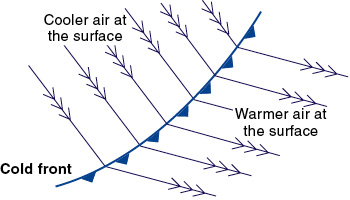

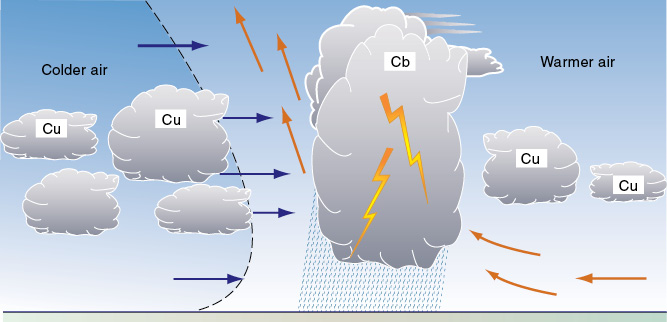

If a cooler air mass undercuts a mass of warm air and displaces it at the surface, a cold front is said to occur. The slope between the two air masses in a cold front is generally quite steep (typically 1 in 50) and the frontal weather may occupy a band of only 30 to 50 nautical miles.

The boundary between the two air masses at the surface is shown on weather charts as a line with barbs pointing in the direction of travel of the front. The cold front moves quite rapidly, with the cooler frontal air at altitude lagging behind that at the surface.

The air that is forced to rise with the passage of a cold front is unstable and so the clouds that form are cumuliform in nature, cumulus and cumulonimbus. Severe weather hazardous to aviation, such as thunderstorm activity, squall lines, severe turbulence and windshear, may accompany the passage of a cold front.

Figure 17-19 Depiction of a cold front on a weather chart.

Figure 17-20 Cross-section of a cold front.

The Cold Front from the Ground

The atmospheric pressure will fall as a cold front approaches and the change in weather with its passage may be quite pronounced. There may be cumulus and possibly cumulonimbus clouds with heavy rain showers, thunderstorm activity and squalls, with a sudden drop in temperature and change in wind direction as the front passes (the direction shifting clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere, and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere).

The cooler air mass contains less moisture than the warm air, and so the dewpoint temperature after the cold front has passed is lower. Once the cold front has passed, the pressure may rise rapidly. The general characteristics of a cold front are:

- cumuliform clouds — cumulus, cumulonimbus;

- a sudden drop in temperature, and a lower dewpoint temperature;

- possible low-level windshear as or just after the front passes;

- a veering of the wind direction; and

- a falling atmospheric pressure that rises once the front is past.

The Cold Front from the Air

Flying through a cold front may require diversions to avoid weather. There may be thunderstorm activity, violent winds (both horizontal and vertical) from cumulonimbus clouds, squall lines, windshear, heavy showers of rain or hail, and severe turbulence. In some instances, icing could be a problem. Visibility away from the showers and the clouds may be quite good, but it is still a good idea for a pilot to consider avoiding the strong weather activity that accompanies many cold fronts. A squall line may form ahead of the front.

Figure 17-21 Thickening low cloud preceding a cold front.

The Occluded Front

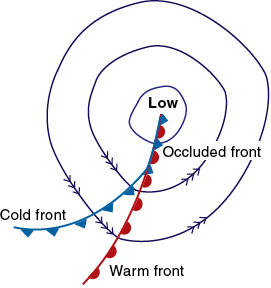

Because cold fronts usually travel much faster than warm fronts, it often happens that a cold front overtakes a warm front, creating an occlusion (or occluded front). This may happen in the final stages of a frontal depression (which is discussed shortly). Three air masses are involved and their vertical passage, one to the other, will depend on their relative temperatures. The occluded front is depicted by a line with alternating barbs and semicircles pointing in the direction of motion of the front.

Figure 17-22 An occluded front on a weather map.

The clouds that are associated with an occluded front will depend on what clouds are associated with the individual cold and warm fronts. It is not unusual to have cumuliform clouds from the cold front as well as stratiform clouds from the warm front. Sometimes the stratiform clouds can conceal thunderstorm activity. Severe weather can occur in the early stages of an occlusion as unstable air is forced upward, but this period is often short.

Flight through an occluded front may involve encountering intense weather, as both a cold front and a warm front are involved, with a warm air mass being squeezed up between them. The wind direction will be different on either side of the front.

Figure 17-23 Cross-sections of occluded fronts.

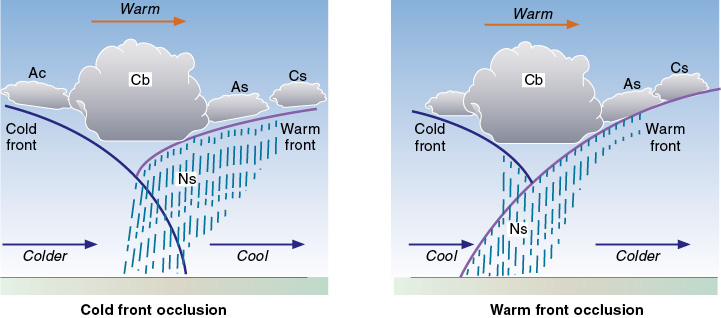

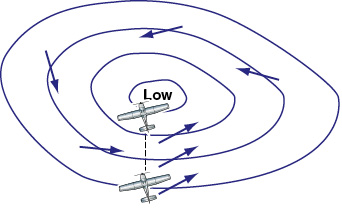

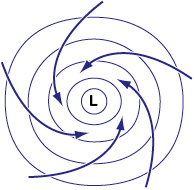

Depressions — Areas of Low Pressure

A depression or low is a region of low pressure at the surface, the pressure gradually rising as you move away from its center. A low is depicted on a weather chart by a series of concentric isobars joining places of equal sea level pressure, with the lowest pressure in the center. In the Northern Hemisphere, winds circulate counterclockwise around a low. Flying toward a low, an airplane will experience right drift.

Figure 17-24 A depression or low pressure system.

Depressions generally are more intense than highs, being spread over a smaller area and with a stronger pressure gradient (change of pressure with distance). The more intense the depression, the “deeper” it is said to be. Lows move faster across the face of the earth than highs and do not last as long.

Figure 17-25 The three-dimensional flow of air near a low.

Because the pressure at the surface in the center of a depression is lower than in the surrounding areas, there will be an inflow of air, known as convergence. The air above the depression will rise and flow outward.

The three-dimensional pattern of airflow near a depression is:

- convergence (inflow) in the lower layers;

- rising air above; and

- divergence (outflow) in the upper layers.

The depression at the surface may in fact be caused by the divergence aloft removing air faster than it can be replaced by convergence at the surface.

Weather Associated with a Depression

In a depression, the rising air will be cooling and so clouds will tend to form. Instability in the rising air may lead to quite large vertical development of cumuliform clouds accompanied by rain showers. Visibility may be good (except in the showers), since the vertical motion will tend to carry away all the particles suspended in the air.

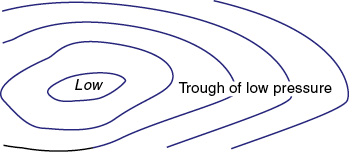

Troughs of Low Pressure

A V-shaped extension of isobars from a region of low pressure is called a trough. Air will flow into it (convergence will occur) and rise. If the air is unstable, weather similar to that in a depression or a cold front will occur, cumuliform clouds, possibly with cumulonimbus and thunderstorm activity.

The trough may in fact be associated with a front. Less prominent troughs, possibly more U-shaped than V-shaped, will generally have less severe weather.

Figure 17-26 A trough.

The Wave or Frontal Depression

The boundary between two air masses moving (relative to one another) side by side is often distorted by the warmer air bulging into the cold air mass, with the bulge moving along like a wave. This is known as a frontal wave. The leading edge of the bulge of warm air is a warm front and its rear edge is a cold front.

The pressure near the tip of the wave falls sharply and so a depression forms, along with a warm front, a cold front, and possibly an occlusion. It is usual for the cold front to move faster across the surface than the warm front, but even then, the cold front moves only relatively slowly. Frontal waves can also form on a stationary front.

Figure 17-27 The frontal depression forming.

The Hurricane or Tropical Revolving Storm

Tropical revolving storms are intense cyclonic depressions and can be both violent and destructive. They occur over warm tropical oceans at about 10-20° latitude during certain periods of the year. In the U.S. they occur off the Pacific southwest coast, in the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic Ocean, and in the Caribbean Sea.

Figure 17-28 A tropical revolving storm or hurricane.

Occasionally, weak troughs in these tropical areas develop into intense depressions. Air converges in the lower levels, flows into the depression and then rises — the warm, moist air forming large cumulus and cumulonimbus clouds. The deep depression may be only quite small (200-300 NM in diameter) compared to the typical depression in temperate latitudes, but its central pressure can be extremely low.

Winds in hurricanes can exceed 100 knots, with heavy showers and thunderstorm activity becoming increasingly frequent as the center of the storm approaches. Despite the strong winds, hurricanes move quite slowly and usually only dissipate after encountering a land mass, which gradually weakens the depression through surface friction. They are then usually classified as tropical storms.

The eye of a hurricane is often only some 10 NM in diameter, with light winds and broken clouds. It is occupied by warm subsiding air, which is one reason for the extremely low pressure. Once the eye has passed, a strong wind from the opposite direction will occur. In the Northern Hemisphere, pronounced right drift caused by a strong wind from the left will mean that the eye of the hurricane is ahead (and vice versa in the Southern Hemisphere).

In addition to the term hurricane, the tropical revolving storm is also known by other names in different parts of the world — tropical cyclone in Australia and the South Pacific, and typhoon in the South China Sea.

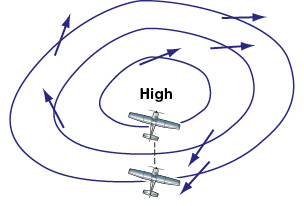

Anticyclones —Areas of High Pressure

An anticyclone or high is an area of high pressure at the surface surrounded by roughly concentric isobars. Highs are generally greater in extent than lows. Yet they have a weaker pressure gradient and are slower moving, although more persistent and longer-lasting. In the Northern Hemisphere, the wind circulates clockwise around the center of a high. Flying toward a high an aircraft will experience left drift.

Figure 17-29 The anticyclone or “high.”

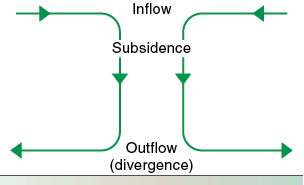

The three-dimensional flow of air associated with an anticyclone is:

- an outflow of air from the high pressure area in the lower layers (divergence);

- the slow subsidence of air over a wide area from above; and

- an inflow of air in the upper layers (convergence).

Figure 17-30 The three-dimensional flow of air near a high.

The high pressure area at the surface originates when the convergence in the upper layers adds air faster than the divergence in the lower layers removes it.

Weather Associated with a “High”

The subsiding air in a high pressure system will be warming as it descends and so any clouds will tend to disperse as the dewpoint temperature is exceeded and the relative humidity decreases. Subsiding air is stable. It is possible that the subsiding air may warm sufficiently to create an inversion, with the upper air warming to a temperature higher than that of the lower air, and possibly causing stratiform clouds to form (stratocumulus, stratus) and/or trapping smoke, haze and dust beneath it. This can happen in winter in some parts of the country, leading to rather gloomy days with poor flight visibility. In summer, heating by the sun may disperse the clouds, leading to a fine but hazy day.

If the sky remains clear at night, greater cooling of the earth’s surface by radiation heat-loss may lead to the formation of fog. If the high pressure is situated entirely over land, the weather may be dry and cloudless, but with any air flowing in from the sea, extensive stratiform clouds in the lower levels can occur.

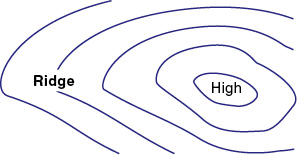

A Ridge of High Pressure

Isobars which extend out from a high in a U-shape indicate a ridge of high pressure (like a ridge extending from a mountain). Weather conditions associated with a ridge are, in general, similar to the weather found with anticyclones.

Figure 17-31 A ridge.

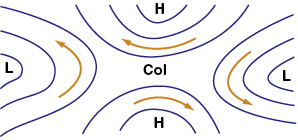

A Col

The area of almost constant pressure (and therefore indicated by a few widely spaced isobars) that exists between two highs and two lows is called a col. It is like a “saddle” on a mountain ridge. Light winds are often associated with cols, with fog a possibility in winter and high temperatures in summer possibly leading to showers or thunderstorms.

Figure 17-32 A col.

Review 17

Wind, Air Masses, and Fronts

1. What is the stratosphere?

2. What are the characteristics of the stratosphere?

3. Will stable air tend to keep rising if it is forced aloft?

4. Will unstable air tend to keep rising if it is forced aloft?

5. What is the primary cause of all changes in weather?

6. What is the Coriolis force?

7. What effect does the Coriolis force have?

8. What effect does friction have on surface winds?

9. While the winds at 2,000 feet AGL and above tend to flow parallel to the isobars, the surface winds tend to cross the isobars at an angle toward the lower pressure. Why?

10. At any level in the atmosphere, windshear can be associated with any change in:

a. wind speed.

b. wind direction.

c. wind speed or wind direction.

d. none of the above.

11. If a strong temperature inversion exists, is a strong windshear possible as you pass through the inversion layer?

12. Which of the following can windshear be associated with?

a. Low-level temperature inversion.

b. Jet stream.

c. Frontal zone.

13. What sort of windshear is likely within and near a thunderstorm?

14. With a warm front, the most critical period for low-level windshear above an airport is:

a. before the warm front passes.

b. after the warm front passes.

15. With a cold front, the most critical period for low-level windshear above an airport is:

a. just before or as the cold front passes.

b. as or just after the cold front passes.

16. What is an air mass?

17. What sort of change will always occur whenever a front passes?

18. Squall lines often develop ahead of a:

a. cold front.

b. warm front.

19. Frontal waves normally form on which of the following?

a. Fast moving cold fronts.

b. Slow moving cold fronts.

c. Stationary fronts.

20. When passing through an abrupt windshear which involves a shift from a tailwind to a headwind, what will tend to happen to your airspeed? How is a constant airspeed maintained in this circumstance?

21. When passing through an abrupt windshear which involves a shift from a headwind to a tailwind, what will tend to happen to your airspeed? How is a constant airspeed maintained in this circumstance?

22. While flying a 3° glide slope, a headwind shears to a tailwind. What will happen to your airspeed and pitch attitude? Will the tendency be to go above or below slope?

23. While flying a 3° glide slope, a tailwind shears to a headwind. What will happen to your airspeed and pitch attitude? Will the tendency be to go above or below slope?

24. Describe what power management would normally be required to maintain a constant indicated airspeed and ILS glide slope when passing through an abrupt windshear which involves a shift from a tailwind to a headwind. Compared to an approach in calm conditions, what will be the power setting in relation to the normal power setting:

a. before the shear is encountered?

b. when the shear is encountered?

c. after the shear is encountered?

25. At which levels in the atmosphere can windshear occur?